ISSN: 2007-7033 | No. 59 | e1407 | Open section: research articles

Innovation through Web 2.0 to support English language learning

Innovación mediante la Web 2.0 como apoyo al aprendizaje del idioma inglés

Kristian Armando Pineda Castillo*

This investigation had the purpose of understanding how the use of a website created by the teacher-researcher contributed to an improvement in the educational experience in English language teaching with Mexican high schoolers. The inquiry undertook a qualitative methodology following an action research design tied to the critical educational science paradigm. Results revealed that the online site encouraged a positive educational experience by attending to the learners’ interests and needs, offering support, an easy navigational interface, and a good experience in the study of English. Furthermore, the internet site was perceived as highly supportive as the subject’s contents were organized by levels and topics, where videos were available to explain each linguistic item clearly. In conclusion, it can be said that the intervention benefited the teenagers’ formation since the website favored their learning of the foreign language with the support that it provided, the simple navigation, the pedagogical approach, and the personal touch employed by the teacher.

Keywords:

educational technology, language instruction, online learning, linguistics

Esta investigación tuvo el propósito de comprender cómo el uso de una página web creada por el docente-investigador contribuyó a una mejora de la experiencia educativa en la enseñanza del idioma inglés con estudiantes de bachillerato mexicanos. La indagación emprendió una metodología cualitativa siguiendo un diseño de investigación-acción ligado al paradigma de la ciencia educativa crítica. Los resultados revelaron que el sitio en línea fomentó una experiencia educativa positiva al atender los intereses y las necesidades de los educandos al ofrecer apoyo, una interfaz de navegación fácil y una buena experiencia en el estudio del inglés. Además, el sitio de internet se percibió como una gran ayuda, ya que los contenidos de la asignatura estuvieron organizados por niveles y temas, y hubo videos disponibles para explicar cada componente lingüístico con claridad. En conclusión, la intervención benefició la formación de los adolescentes dado que el sitio web favoreció el aprendizaje de la lengua extranjera gracias a la navegación sencilla, el enfoque pedagógico y el toque personal empleado por el maestro.

Palabras clave:

tecnología educativa, internet, enseñanza de idiomas, aprendizaje en línea, lingüística

Submitted: February 4, 2022| Accepted for publication: June 29, 2022 |

Published: July 1st, 2022

Citation: Pineda Castillo, K. A. (2022). Innovation through Web 2.0 to support English language learning. Sinéctica, Revista Electrónica de Educación, (59), e1407. https://doi.org/10.31391/S2007-7033(2022)0059-005

* PhD in Education from the Instituto de Estudios Superiores en Educación por Competencias. Professor at the Colegio de Bachilleres del Estado de Sinaloa and thesis director at the Universidad Pedagógica del Estado de Sinaloa. Research areas: innovation in educational processes through critical, theoretical and practical reflection. E-mail: kristian.pineda@upes.edu.mx y kapineda@cobaes.edu.mx /https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4686-3587

Introduction

The study addressed in this paper revolves around an educational project that has been built since the year 2020. The project is inserted into a technological dimension by employing Web 2.0 to transform language education in public Mexican high school settings in the state of Sinaloa. Such a change is a matter of praxis, where the application of theory and knowledge converge in a transdisciplinary way in the creation and use of the website Learn English with Kris (LEK) for adolescents as a support for English learning.

This research takes place in two schools incorporated into the Mexican educational system under the name of Colegio de Bachilleres del Estado de Sinaloa. The first one, high school 1, has a population of 600 students aged 14-18. Nearly 30 teachers form part of the academy, 100% of them have a bachelor’s or engineering degree, and about 20% hold a postgraduate qualification. Furthermore, most learners possess some sort of technological device to connect themselves to the web as they are interested in interacting with their friends and relatives virtually. Also, there are 15 classrooms, a library, a computer lab, and administrative offices that offer different educational services.

The second setting, high school 2, offers two shifts and holds a population of 721 adolescents, all distributed into 22 groups in the morning and seven in the afternoon. There are 60 teachers in total, 100% of them have a professional career, and about 15% hold a postgraduate degree. Furthermore, most learners have technological device that allows them to connect to the internet; in contrast with the first scenario, many of these juveniles are students who are low achievers, and others are usually rejected from other schools due to discipline issues; additionally, many are victims of an undesirable culture as they use drugs or worship drug lords. Moreover, the school has an auditorium, a library, a computer lab, and administrative offices that offer educational services.

With the aim of improving professional practice, weaknesses regarding the teaching of English were investigated through a process of deep reflection and introspection. Such reflection in turn considered formative processes undertaken by the present teacher-researcher in the educational technology field throughout the same two years this project was built. As a result, the creation and use of the website LEK (https://kristiancb.wixsite.com/lekcb) to support foreign language learning was implemented. In this case, grammar is a focus area since the institutional syllabus is based on developing language structural skills in learners.

Hence, the object of study can be determined as the use of Web 2.0 to enhance the English teaching and learning experience of Mexican high schoolers. In the same order of ideas, the main research question was posed as: how does the creation and use of the internet site Learn English with Kris ameliorate the teaching-learning experience of the foreign language? The prior scientific framework gave place to the purpose of the investigation, that is, to understand how the use of an online site created by the teacher-researcher contributes to an improvement in the educational experience in English language teaching with teenagers.

To respond to the central question, a tentative answer was proposed, also alluded to in the qualitative paradigm as a working hypothesis (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2018; Glaser & Strauss, 1967), which was refined throughout the inquiry. The created website LEK fosters a positive educational experience for high school learners by offering different possibilities to learn the English language in academic settings and fostering its use in authentic communicative situations. Moreover, the available resources could be ideal to explain language items in a way that is thought to be best for teenagers, striving to avoid long and dull classes.

Websites for English language teaching

The internet is being used more frequently as a learning tool to help people learn English in the twenty-first century. In that sense, teachers or learners could make use of different types of websites depending on their objectives. Moreover, research has shown how Web 2.0 can contribute to a positive experience when studying the lingua franca. Now, online news, English learning internet sites, and other platforms may be taken advantage of for such purposes (Chang-Chávez, 2017; Maridueña-Macancela, 2019; Nasution, 2019).

Muta & Dennis (2016) carried out research to discover the grammatical tenses used in online news. The experts recommend using news on the internet to expose learners to the target language which will, in turn, help them improve their reading and listening skills, also found as a positive aspect in other studies (Syakur, Fanani & Ahmadi, 2020). This authentic resource may be handy for educators attempting to meet learning objectives; however, the use of strategies such as exposure to stories, songs, and various types of text is strongly advised.

Moreover, some inquiries have demonstrated how online websites strictly focused on academic English can also contribute to language learning in action research studies like this one (Amalia, 2020; Ekaningsih, 2017). A website has the advantage of being able to display information available to users at any time and from any place. Additionally, investigations show how motivation is strongly improved when assessment activities are included since learners become aware of their weaknesses and strengths, but more than that, professors could come up with a strategy to mend such needs (Maridueña-Macancela, 2019; Seifert & Feliks, 2018).

As it is stated by Abe (2020), pupils are more actively involved in their educational process when using websites. Furthermore, this kind of learning promotes independency for individuals as they seek to resolve cognitive challenges through a wide variety of academic tasks by themselves or in a cooperative-collaborative fashion. Concurrently, it is indicated by researchers like Amalia (2020) that online evaluation tools can spark learners’ interest in language learning. However, dynamics must be designed according to the students’ profile, and this is even greatly enhanced if a gamification factor is included in the assessment activities in a competitive, fun, and rewarding atmosphere without a possibility of cheating; some examples of platforms which allow such interaction are Kahoot!, LearnEnglish kids (British Council), Quizizz, among others.

English learning website’s interface

The platform Wix.com, a free website creator, was employed to build the site for this intervention. In that sense, Oliver & Herrington (2001) suggest learning resources, learning tasks, and learning support as elements to consider when a website is used in education. According to the authors, these are essentials now of using Web 2.0 as an educational resource for students to be actively mobilizing their skills and knowledge. Nonetheless, there is no consensus on the way a cyberspace should be created or operated; still, certain design fundamentals were considered for the current investigation such as navigation, graphical representation, organization, content utility, purpose, simplicity, and readability (Garett et al., 2016; García-García, Carrillo-Durán & Tato-Jimenez, 2017).

With the purpose of meeting optimal navigation criteria, the orientations made by Garett et al. (2016) were followed. Thus, a homepage was designed containing all the elements organized in a way for visitors to rapidly identify their interests. The first part presents a brief description of the website and contents of each page, every section including access buttons, giving users control manageability. Also, a menu and a search option were incorporated in case visitors wish to take a shortcut when looking for specific content.

Following Garett et al. (2016), graphical representation was met through the inclusion of images of a reasonable size. In addition, audiovisual content was integrated for high school learners, employing appealing and colorful PowerPoint presentations. Plus, the text and colors were combined in an attractive fashion for the human eye. Likewise, a logo was created with the use of Microsoft Word, parting from the website’s name.

In terms of organization, simple architecture for the building of the website was carried out by fostering a logical structure and organizing content, as suggested by García-García, Carrillo-Durán & Tato-Jimenez (2017). Therefore, the headings and keywords were thought of carefully to label each item or topic to be presented to visitors. Like in navigation, the online page strives to give an easy and understandable view of the information which is offered to learners of English who are Spanish speakers.

Likewise, the orientations provided by Garett et al. (2016) were procured to meet content utility. For this aspect, sufficient information was presented to make sure that learnability could be fostered through the educational videos posted on the website. Consistently, quality was also achieved by using materials ad hoc for teenagers, conforming to the online page’s purpose.

On the other hand, in accordance with the orientations given by Garett et al. (2016), the website’s simplicity was met by using simple subject headings. In addition, wix.com offered an option to see how the internet site looks both on desktop screens or laptops and on portable devices, which allowed an arrangement of the different elements to achieve an easy-to-navigate and friendly interface. Additionally, the purpose of the cyberspace and the target visitors were clearly and explicitly announced on the homepage. Moreover, an “about” section was included, providing a more detailed description of the site as well as contact information to get in touch with the teacher-researcher.

Finally, readability was another aspect that was carefully worked out as the website was thought to be for educational purposes (Garett et al., 2016). For this reason, the text was proofread to make sure syntactic issues were not present. Likewise, grammar and appropriate use of register were checked, as was the coherence of the messages in each of the internet site sections.

Methodology

This investigation was circumscribed under the qualitative approach through an action-research design. The method is grounded in the critical educational science paradigm where researchers may employ both qualitative and quantitative techniques to collect and analyze information, but they should strongly lean towards the first (Ary et al., 2010; Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Leavy, 2017; Stringer, 2007). Thus, the inquiry appealed to participant observation, documentary analysis, and in-depth interviews. Additionally, some numerical analysis is included with the aim of capturing and representing the voices of all the learners.

Action research is a cyclic, systematic, and rigorous investigation methodology that seeks to emancipate, transform, and improve professional practice in the context where it is employed (Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Stringer, 2007). On the other hand, Cohen, Manion & Morrison (2018) indicate how such a method may be represented in different ways depending on the possibilities and design of the inquiry, as it is in the case of this educational intervention where the researcher and learners, as critical thinkers, play a crucial role as stakeholders and validators of knowledge.

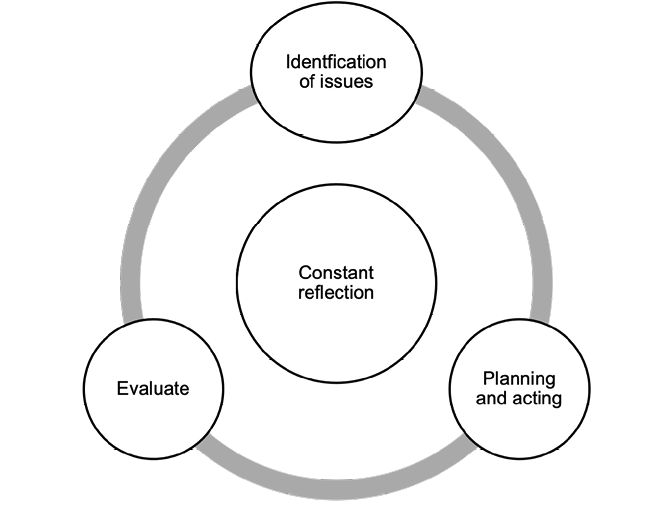

In short, the method can be synthesized in three phases. The first one entailed a process of deep reflection of the teacher’s pedagogical practice, where needs and areas of opportunity were identified. The second step involved building and applying a strategic plan through the organization of the interaction students would have with the website. Finally, the last phase of the methodological route involved carrying out an evaluation of this project through in-depth interviews. A representation of the prior process can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Representation of the action research process.

Sampling. Two purposive sampling procedures were undertaken according to the investigation techniques. The first one was comprehensive sampling, which, as indicated by Ary et al. (2010), means the inclusion of every individual with certain characteristics, in this case, all the students who formed part of the teacher-researcher’s class in 10 prearranged groups. That meant having a total of 408 participants: 222 males and 186 females (Table 1). The foregoing was justified as action research is an inclusive educational methodology (Carr & Kemmis, 1986).

Table 1. Inclusion of participants in comprehensive sampling

|

Number of students |

Males |

Females |

|

|

High school 1 |

|||

|

Group 1 |

52 |

24 |

28 |

|

Group 2 |

51 |

33 |

18 |

|

Group 3 |

50 |

29 |

21 |

|

Group 4 |

42 |

30 |

12 |

|

Group 5 |

42 |

22 |

20 |

|

Group 6 |

43 |

21 |

22 |

|

Group 7 |

43 |

23 |

20 |

|

Group 8 |

43 |

21 |

22 |

|

High school 2 |

|||

|

Group 1 |

22 |

8 |

14 |

|

Group 2 |

20 |

11 |

9 |

Note: This table shows the inclusion of all the 408 students with

participant observation and documentary analysis.

The second procedure was opportunistic sampling, which involves taking the opportunity to include those participants considered important and that are found opportunistically in natural circumstances (Ary et al., 2010; Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2018). In such a case, 20 group leaders, 10 males and 10 females, were selected since their contributions were thought to be extremely valuable for this research as they represented the voices of all students (Table 2).

Table 2. Inclusion of participants in opportunistic sampling

|

Group |

Number of students |

Males |

Females |

|

High school 1 |

|||

|

Group 1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Group 2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Group 3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Group 4 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Group 5 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Group 6 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Group 7 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Group 8 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

High school 2 |

|||

|

Group 1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Group 2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

Note: This table shows the inclusion of the 10 group leaders

representing the students in the 10 groups with in-depth interviews.

Procedure

In order to start off this intervention, group leaders were included as main stakeholders to represent the voices of their classmates in interviews. Nevertheless, the rest of the adolescents were also integrated into the process to analyze the overall impact with research techniques such as documentary analysis and participant observation, which allowed the researcher to capture everybody’s experience. Participants were organized on the social network WhatsApp to foster an easier medium of communication between stakeholders.

In the first stage, areas of opportunities related to English language teaching were reflected upon by means of introspection through reflection on the present teacher-researcher’s own performance. Introspective inquiries provide an insider perspective that allows researchers to report on what educational actors do and why they do it, similar to a self-evaluation; it also answers questions linked to beliefs, putting into reflection the teacher’s role and way of thinking (Dikilitaş & Griffiths, 2017). Such a technique is contemplated as a unique design since it is based on an in-depth study of a single individual (Arnal, del Rincón & Latorre, 1992). Hence, the process of data analysis gave place to the identification of the main field of interest for improving practice in this Mexican high school setting, which justified the use of the action research methodology.

The second research phase required the elaboration and implementation of an action plan. Therefore, the orientations provided by Stringer (2007) and Kemmis, McTaggart & Nixon (2014) were considered to conduct a pertinent investigation. Thus, with the intention of involving stakeholders, a meeting was organized to reach an agreement on the different actions to be executed. Here, observations were recorded based on the experience that learners and the professor-researcher were having throughout the intervention, providing an account of those difficulties encountered.

During the last phase of this action research, in-depth interviews, and documentary analysis were conducted to evaluate the overall intervention. Hence, the analysis techniques appealed to the constructivist grounded theory by using open, focus, and axial coding, as well as the constant comparative method (Bryant, 2017; Charmaz, 2006). Furthermore, computer text processing programs that facilitate the organization of the information were utilized to analyze the data, which is considered valid in qualitative investigations (Cisneros-Puebla, 2003; Watkins, 2017).

Results

Hereunder, the findings of the present action-research process are described in correspondence with the methodological procedure.

Identification of issues

To identify areas of opportunity, the present researcher conducted a documentary analysis appealing to documents of the daily educational practice. In this sense, records in attendance lists of learners’ performance, and reports of academic tutoring were the main initial sources since they show evidence of the adolescents’ daily behavior. In addition, participant observation was carried out through in-depth introspection or autoethnography, which is ideal for qualitative studies of this division (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2018; Hayler, 2011; Yin, 2016). As a result, two categories were identified: students’ short attention span and a need for innovation.

Students’ short attention span. Even when many learners are fond of the teacher-researcher’s style in relation to language instruction, it was observed how others tend to get distracted very easily from classes. In addition, it was noticed that this diversion has been caused by technological tools such as cell phones and social networks, videogames on the same mobile devices, or friends. Additionally, a feeling of boredom and disinterest towards the English class was identified.

A need for innovation. Staying in a traditional old school model of education cannot continue in a digital age where Web 2.0 takes part in almost any human activity. For such a reason, it is fundamental to carry out educational processes that involve the use of technological devices in an ambience that incorporates all the facilities to have access to knowledge, in this case, to language instruction. Thus, because teenagers have a common interest in looking for information on the internet, the present researcher embarked on an enterprise of abandoning routine practices by creating and launching a website to support English language learning, as it would be a resource of permanent benefit not only for these communities but also for the worldwide Spanish speakers.

Planning and acting

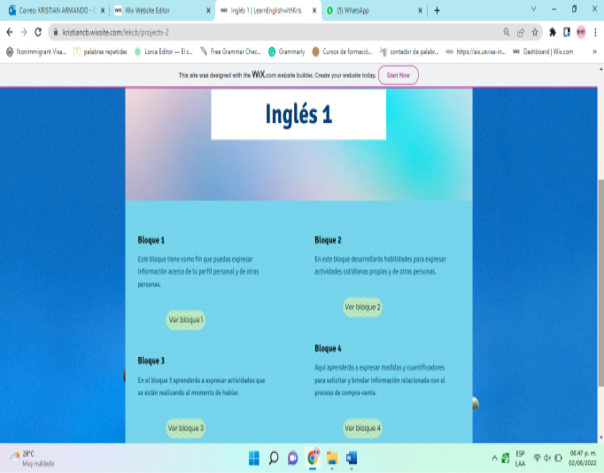

In terms of planning, an action plan was devised in consonance with the orientations made by Stringer (2007) and Kemmis, McTaggart & Nixon (2014). The planned activities involved organizing the educational interaction and consolidating the website LEK from February to July of 2020; nonetheless, the online site’s interface and content kept on being updated throughout the implementation of the project (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Screenshot of the interphase of one of the website’s sections.

Note: This is a screenshot retrieved from the wix.com platform.

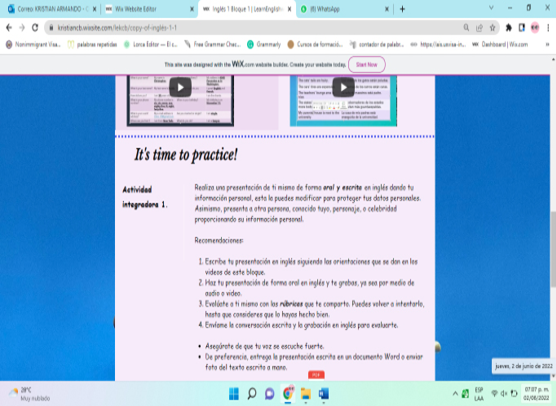

Throughout the first period of the intervention, from August to December 2020, high schoolers were mainly asked to use the website to consult the provided resources for them to do the integrative activities and online quizzes designed by the teacher-researcher (Figure 3). Also, learners were invited to voluntarily visit the internet site whenever they needed to review a specific topic; additionally, classes were imparted by projecting the created videos synchronously. Until then, the multimedia material proved to be helpful; nevertheless, notwithstanding students had this support, many required additional assistance on behalf of the professor to improve on their English productive skills: writing and speaking.

Figure 3. Screenshot of integrative activities fostered through the website.

Note: This is a screenshot retrieved from the wix.com platform.

During the second moment of the intervention, from January to June of 2021, students had acquired an English coursebook provided by the institution, which meant that it had to be incorporated into the teaching process in addition to other learning activities. Many applied linguistic experts offer arguments for and against the use of coursebooks (Travé-González et al., 2017); however, in this case, it was necessary to include it in the pedagogical practice because juveniles were required to purchase it by the high school system. Therefore, adolescents had to be given homework in the book, and the greatest asset to aid them was the created website, since they had the opportunity to access the content at any time and place, ubiquitously. Still, like in the first period, some teenagers needed academic tutoring to complete their assignments.

Project evaluation

Twenty in-depth interviews, participant observation, and documentary analysis were conducted in the evaluation phase. Along with the inquiry, data analysis techniques borrowed from the grounded theory methodology gave place to postulate a theoretical hypothesis that demonstrates the understanding of the impact of Web 2.0 on the students’ educational experience in English language learning.

Substantive theory. The creation and use of websites for English language learning fosters a positive educational experience in high schoolers as they tackle the learners’ interests and needs, especially when the creator is the students’ teacher. Furthermore, created multimedia material can explain grammatical items clearly as it could include the teacher’s personal touch, but in a digital dimension. Additionally, learning activities designed by the educator may promote a good experience since the resources would be intended to support the learning of content not only in academic but in authentic situations.

Three main categories were identified during the analysis of the in-depth interviews: support, easy navigation, and good learning experience.

Support. The website LEK served as a support for learners to do integrative activities and other homework assignments in the book. According to the responses in the in-depth interviews, quite a few teenagers frequently consulted the videos available on the online site. This was a great advantage for them, seeing that they could go over the English class or explanations as many times as they wanted. Therefore, learning vocabulary and other linguistic items was perceived to be easier. Next, a comment made by an adolescent demonstrates such an aspect: “… you explain very well in your videos. What I like about them is that I can play them repeatedly. Another thing is that you managed to organize the videos according to the subject’s blocks, which makes them easy for us to find on the website” (student 19).

Easy navigation. According to the analyzed answers, the organization of the resources allowed learners to navigate easily on the website LEK. This was perceived to be the result of the management of the different sections and the access options found on the homepage and menu. Next, an adolescent expressed such an aspect in a contribution made in an interview: “… there are many shortcuts to get to the videos I feel like watching or the activities I need to do. For example, I can just use the homepage buttons to find my class, or I can use the search bar and type in the name of the topic I want to learn about” (student 4).

Good learning experience. Most learners highlighted the fact that the multimedia material clearly explained linguistic items of the English subject, which facilitated learning. According to the adolescents, the teaching methodology applied by the teacher played a major role in the foregoing since the examples and language used were appropriate for them. A student reported this as follows: “… the examples you provide are attractive and simple for us to understand. Another important element here is how you teach your class, as you first present the topic, then give examples, and finally, you employ a dynamic way to practice the learnt content” (student 18).

On the other hand, the integrative activities were ideal since they required learners to incorporate the knowledge acquired in each block, promoting the use of the foreign language in real-life communicative situations. Also, the evaluation instruments were clear and facilitated the elaboration of every activity. A juvenile expressed the following on this matter: “… I think that those integrative activities are interesting. Sometimes I feel that the rubrics are complicated but, at the same time, necessary because we can use them to see how we did on the homework; plus, we can have an idea of what grade we could get” (student 5).

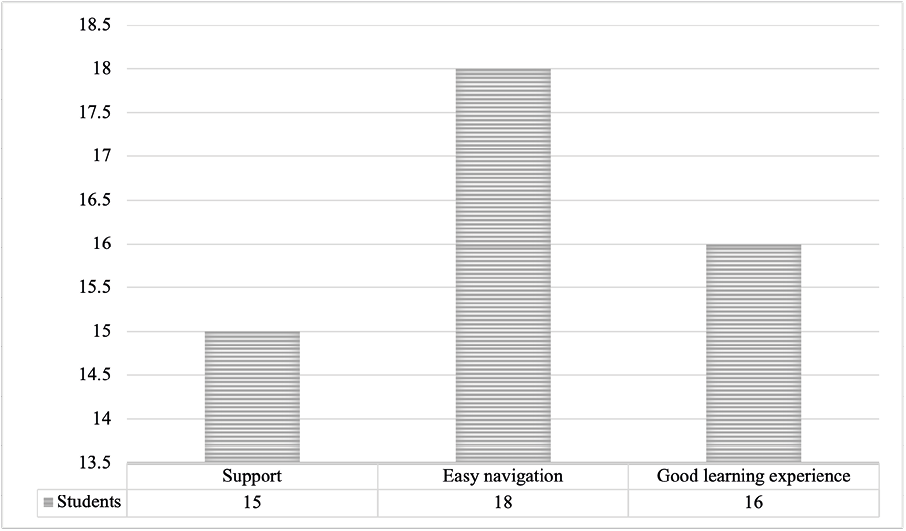

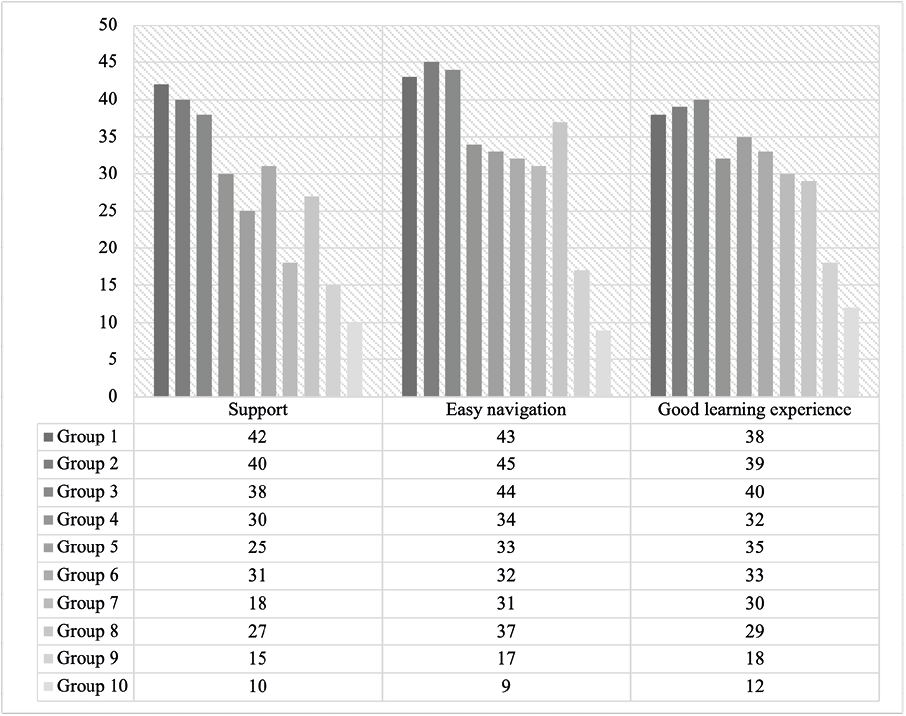

Furthermore, with the intention of including the contributions made by all learners, answers in all in-depth interviews were coded and grouped into the following categories: support, easy navigation, and good learning experience. Now, qualitative research is considered to be of narrative or dialectical nature, striving to understand the feelings of individuals and problematics; however, this investigation is circumscribed in the critical educational science where other methods of analysis can be used (Stringer, 2007). Therefore, percentages were calculated according to the number of concurrences for each category. Such information has the sole purpose of including the responses of the 20 students (Figure 4), and in no way has the objective of measuring variables like in an experimental design.

Figure 4. Impact on English language learning with the use of the created website.

Note: The figure represents responses’ concurrences of the 20 interviewed students.

As it can be seen, most learners found the website easy to navigate. Also, many expressed that it offered support to learning activities. Finally, it can be appreciated how quite a few lived a positive educational experience in the learning of English as a foreign language with the use of this technological resource created by the teacher-researcher.

Parallel to the prior, information from participant observation and documentary analysis was put together by appealing to records of attendance lists of adolescents’ performance and academic tutoring reports, together with the data analyzed in interviews. During observation, oral or written participation was registered as usual, but a slight increase in participation was noticed; also, students turned in more assignments that required the use of the website. In the case of academic tutoring, apart from the assessment given face to face, the website was employed as a support for them to review the topic covered and accomplish pending tasks. Therefore, for both types of documents, the coded units of analysis were integrated into the main categories, which was useful to evaluate the impact of the strategy on the 408 students in both high school settings. In total, it was interpreted that 325 learners found the website’s interface easy to navigate, 306 were observed to have had a good learning experience, and 276 used the online site to support their study of English (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Impact on English language learning with the use of the created website.

Note: The figure embodies answers’ concurrences of the 408 students.

The overall qualitative and numerical data gives rise to an interpretation of a positive impact caused on high schoolers on the learning experience of English as a foreign language. At the same time, it can be said that the research process does not end here, but it is fundamental to disseminate the findings made up to this point for other educators to consider the importance of innovation through Web 2.0.

Discussion

The main limitation of this project was the fact that not all the participants had an internet connection at home or did not have the technological tools to do their homework assignments. Unfortunately, very few options existed to face these issues. In this case, they were advised to ask family members for support by borrowing a cellphone or computer, while others had to be suggested to go to a cybercafé or a public place which offered free access to the web. Such recommendations were the perfect solution for some students, but not for the ones who had no high-tech devices.

Another limitation was that the platform Wix.com requires a payment to get a domain in order to appear in search engines like Google, Yahoo, Microsoft Bing, Baidu, among others, but it does allow the use of the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) (https://kristiancb.wixsite.com/lekcb). Unfortunately, the attainment of the domain entailed an economic investment which was out of the researcher’s hands. Still, the internet site was promoted in academy meetings with other English teachers and students by sharing the URL; nonetheless, individuals who are not part of the teacher’s class cannot find the website unless they have the web address.

Several websites have been created for the public, but there are a few that adopt a contextualized dynamic. Such an aspect may be perhaps one of the main disadvantages of the website Learn English with Kris because even though the online site was designed for the high schoolers that are part of the present intervention, the content that is included may not reach different educational settings around the world. For example, the multimedia material and the academic activities were pedagogically produced for students who are Spanish speakers, which leaves aside other communities. However, as far as the present researcher can tell, the impact of the internet site could be expanded not only to the scenarios laid out in this paper, but to a national or even international level.

When this issue is contrasted with other platforms which are designed to be applied universally, it might be thought that the website LEK makes no major contribution. Nevertheless, it must be remembered that education is a context-specific act where educators need to think and surpass the status quo to improve educational quality. This, according to the philosophical principles of the critical educational science postulated by Carr & Kemmis (1986) and Stringer (2007), means the emancipation of the teacher-researcher to more than a technician, a leader in education that strives to enhance practice through innovation and research from a critical point of view that parts from reflection and praxis.

Conclusions

It can be concluded that the website Learn English with Kris favored the experience in the study of English. This was possible since it offered support to academic activities through its navigation interface, it also employed an appropriate pedagogical approximation, and an acceptable personal touch by the teacher-researcher. Thereby, the process allowed the achievement of the general research purpose of understanding how the use of the online site fostered a positive educational experience for high school students.

It is vital to assert that research will continue by updating the content and activities on the website with the aim of developing different linguistic skills. Consequently, the following questions are proposed: 1) How can an internet site created collaboratively by many language educators contribute to the educational experience of a whole school system? and 2) how can a project of such magnitude transform the teachers’ praxis in education? These and more inquiries could be devised, but it is up to educators and other main stakeholders to look forward to abandoning the status quo through innovative and reflective practice.

Results in this article attempt to establish no general truths, seeing that action research is mostly taken as a context-specific investigation methodology which is grounded on the critical educational science. In such matters, researchers are invited to carry out investigations by referring to this research design, but results may be different depending on every pedagogical scenario.

Another important conclusion to draw is that innovation is not just an application of technology. It is the act of knowing how to apply it. It demands a humanistic element in its creation and application for it to be successfully accepted by all the members of a community. This acceptance is vital to completing the transition to the digital era, where if technology were to be applied in a cold manner to individuals, it could put them at the risk of being abandoned. In this case, Web 2.0 has come to be a powerful asset to education, allowing students to access knowledge that contributes to the teaching and learning of English as a foreign language.

References

Abe, J. A. (2020). Big five, linguistic styles, and successful online learning. The Internet and Higher Education, vol. 45, núm. 100724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100724

Amalia, D. F. (2020). Quizizz website as an online assessment for English teaching and learning: Students’ perspectives. Jo-ELT (Journal of English Language Teaching) Fakultas Pendidikan Bahasa & Seni Prodi Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris IKIP, vol. 7, núm. 1, pp. 1-8. https://doi.org/10.33394/jo-elt.v7i1.2638

Arnal, J., del Rincón, D. & Latorre, A. (1992). Investigación educativa: Fundamentos y metodología. Editorial Labor, SA.

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Sorensen, C. & Razavieh, A. (2010). Introduction to research in education (eight edition). Wadsworth, CENGAGE Learning.

Bryant, A. (2017). Grounded theory and grounded theorizing: Pragmatism in research practice. OXFORD.

Carr, W. & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge, and action research. Routledge/Falmer.

Chang-Chávez, C. C. (2017). Uso de recursos y materiales didácticos para la enseñanza de inglés como lengua extranjera. Pueblo Continente, vol. 28, núm. 1, pp. 261-289. http://200.62.226.189/PuebloContinente/article/view/772

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE.

Cisneros-Puebla, C. A. (2003). Analisis cualitativo asistido por computadora. Sociologias, vol. 5, núm. 9, pp. 286-313. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=86819565014

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (eight edition). Routledge, Taylor, and Francis Group.

Dikilitaş, K. & Griffiths, C. (2017). Developing language teacher autonomy through action research. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ekaningsih, N. (2017). Enhancing students’ English grammar ability with online website link. EduLite: Journal of English Education, Literature and Culture, vol. 2, núm. 2, pp. 431-444. http://dx.doi.org/10.30659/e.2.2.431-444

García-García, M., Carrillo-Durán, M. V. & Tato-Jimenez, J. L. (2017). Online corporate communications: Website usability and content. Journal of Communication Management, vol. 21, núm. 2, pp. 140-154. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-08-2016-0069

Garett, R., Chiu, J., Zhang, L. & Young, S. D. (2016). A literature review: Website design and user engagement. Online journal of communication and media technologies, vol. 6, núm. 3, pp. 1-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4974011/

Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction.

Hayler, M. (2011). Autoethnography, self-narrative and teacher education. Sense Publishers.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R. & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Springer.

Leavy, P. (2017). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, community-based participatory research approaches. The Guildford Press.

Maridueña-Macancela, J. (2019). Websites as support tools for learning the English language. Journal of Science and Research, vol. 4, núm. 2, pp. 13-20. https://revistas.utb.edu.ec/index.php/sr/article/view/322

Muta, J. & Dennis, N. (2016). A study of tenses used in English online news website. International Journal of Research -GRANTHAALAYAH, vol. 4, núm. 7, pp. 248-258. https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v4.i7.2016.2617

Nasution, A. K. R. (2019). YouTube as a media in English Language Teaching (ELT) context: Teaching procedure text. Utamax: Journal of Ultimate Research and Trends in Education, vol. 1, núm. 1, pp. 29-33. https://doi.org/10.31849/utamax.v1i1.2788

Oliver, R. & Herrington, J. (2001). Teaching and learning online: A beginner’s guide to e-learning and e-teaching in higher education. Centre for Research in Information Technology and Communications, Edith Cowan University.

Seifert, T. & Feliks, O. (2018). Online self-assessment and peer-assessment as a tool to enhance student-teachers’ assessment skills. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 44, pp. 169-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1487023

Stringer, E. T. (2007). Action research (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Syakur, A., Fanani, Z. & Ahmadi, R. (2020). The effectiveness of reading English learning process based on Blended Learning through “Absyak” website media in higher education. Budapest International Research and Critics in Linguistics and Education Journal, vol. 3, núm. 2, pp. 763-772. https://doi.org/10.33258/birle.v3i2.927

Travé-González, G., Pozuelos-Estrada, F., & Travé-González, G. (2017). How teachers design and implement instructional materials to improve classroom practice. Intangible Capital, vol. 13, núm. 5, pp. 967-1043. http://dx.doi.org/10.3926/ic.1062

Watkins, D. C. (2017). Rapid and rigorous qualitative data analysis: The “RADaR” Technique for applied research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 16, pp. 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917712131

Yin, R. K. (2016). Qualitative research from start to finish (second edition). The Guilford Press.