ISSN: 2007-7033 | Núm. 62 | e1612 | Open section: research articles

Perceptions towards public English as a foreign

language education in Mexico: Insights

from secondary school learners

Enseñanza pública del inglés en México:

percepciones de los estudiantes de secundaria

Alicia Manrique*

Jesús Izquierdo**

Exploring students’ perceptions of English as a foreign language learning serves to understand the achievements of public education. This study examines the perceptions of public secondary learners in Mexico. These research questions were addressed: What kind of perceptions do secondary school students have about learning English in public education? How does their language proficiency affect these perceptions? To answer these questions, a quantitative descriptive study was carried out with 114 students of 2nd grade in a public secondary in Tabasco. The participants completed three quantitative instruments: a sociodemographic survey, to document their background in English and general information; an English test, to classify them into different language proficiency levels, and a four-point Likert-type questionnaire, to identify their perceptions about learning English. The results reveal that students with greater competence have better perceptions about learning English in public education and that perceptions about achievements and learning tasks vary with competence, highlighting the importance of research around key actors in education: the student, as well as the selection of strategies to improve their language skills and perceptions about English as a foreign language learning in public education.

Keywords:

English as a foreign language learning, learner perception, secondary education, Mexican public education

Explorar las percepciones del alumno sobre el aprendizaje del idioma inglés como lengua extranjera sirve para comprender los logros de la educación pública. Este estudio examina dichas percepciones en la educación secundaria pública en México. Se abordan las preguntas de investigación: ¿qué tipo de percepciones tienen los estudiantes de secundaria pública sobre su aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera? ¿Cómo afecta su dominio del idioma inglés a estas percepciones? Para responderlas, se realizó un estudio descriptivo cuantitativo con 114 estudiantes de segundo grado en una secundaria pública de Tabasco. Se completó con tres instrumentos cuantitativos: una encuesta sociodemográfica para documentar sus antecedentes en inglés e información general; una prueba de inglés para clasificarlos en diferentes niveles de competencia lingüística; y un cuestionario de tipo Likert de cuatro puntos para identificar sus percepciones sobre el aprendizaje del inglés. Los resultados revelan que los estudiantes con mayor competencia tienen mejores percepciones sobre el aprendizaje del idioma inglés y que las percepciones sobre los logros y las tareas de aprendizaje varían con la competencia; resalta la importancia de la investigación en torno a los actores clave en la educación: el estudiante, así como la selección de estrategias para mejorar sus habilidades lingüísticas y percepciones sobre el aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera en la educación pública.

Palabras clave:

aprendizaje del inglés, percepciones de estudiantes, educación secundaria, educación pública en México

Submitted: July 21, 2023 | Accepted for publication: January 23, 2024 |

Published: January 30, 2024

Citation: Manrique, A. & Izquierdo, J. (2024). Perceptions towards public English as a foreign language education in Mexico: Insights from secondary school learners. Sinéctica, Revista Electrónica de Educación, (62), e1612. https://doi.org/10.31391/S2007-7033(2024)0062-006

* She's currently a doctoral candidate in the PhD in Educational Studies at Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco. Her research interest focuses on the learning and teaching of English in public secondary education through Content-based Instruction. E-mail: alicel1308@hotmail.com

** He holds a PhD in Second Language Education (McGill University, Canada) and is now full professor at Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco. He holds an appointment as a National Researcher (SNI 2) from the Sistema Nacional de Investigadores of the National Research Council of Mexico (CONAHCyT). His teaching and research focus on the teaching and learning of English and French in classroom contexts, technology-enhanced language teaching, foreign language teacher education, language policy and planning, and quantitative methods in language education research. E-mail: jesus.izquierdo@mail.mcgill.ca/ https://jesusizquierdo.net

Introduction

Many nations have incorporated English as a foreign language (EFL) into public education. Consequently, English language learning has become a matter of importance for students enrolled in kindergarten, elementary, secondary, and higher education. Countries have implemented guidelines, goals, and evaluation criteria based on the European Framework of reference (CEFR) (Izquierdo et al., 2021). The CEFR presents a series of benchmarks to determine the level of competence in a language; these benchmarks have been adopted in Mexico and other parts of the world. The benchmarks start from level A1 (low proficiency) to level C2 (the highest proficiency level) (http://www.commoneuropeanframework.org/).

In Mexico, for instance, public education students are expected to reach a B1 language proficiency level by the end of secondary education. Nonetheless, official reports indicate that Mexico ranks 88th out of 111 countries evaluated in terms of English language proficiency (Education First [EF], 2022). In Latin America (Education First, 2021), Mexico ranks 19th among the 20 countries evaluated. The 2023 reports corroborate the unsuccessful results obtained in EFL learning in secondary learners because, nowadays, Mexico is in the place 89th from about 113 countries evaluated. The statistical reports point to a decreasing trend in the EFL proficiency level of learners in public education. These results indicate that the students in Mexico are not reaching the proficiency levels that are expected from the Minister of Education. Moreover, the national statistics show that a small number of people speak English in Mexico (INEGI, 2019). These reports instantiate the claim that the English language proficiency is far from achieving a valuable stand in Mexico (Charles & Torres, 2022).

Possible reasons for these results relate to school conditions, such as time, class size, mixed ability classes and available resources (González, 2009; González et al., 2004). Velázquez (2013) and Izquierdo et al. (2016) argue that the teaching of English in Mexico has focused on the structural elements of the language for decades, even though different educational reforms have emphasized the need to promote communication in the classroom. The reforms have not fully permeated the teaching-learning processes of the public secondary schools, neither in urban nor in rural areas (Hernández & Izquierdo, 2020; Izquierdo et al., 2016, 2021). The teaching of English focuses too much on memorization and decontextualized use of the language. The authors assert that the teaching continues to stagnate due to the lack of didactic foundations that guide the student to practice the language in different social contexts. Izquierdo et al. (2014) further emphasize the need for teachers to diversify contents and contexts that favor the integration of the English language with the other fields of the curriculum. Jaime et al. (2021) advocate that the teaching and learning of English in Mexico needs to incorporate didactic strategies activities and resources that are in line with the context, knowledge, interests, learning, styles, emotions, beliefs, values, discourses, and motivation of students. The arguments have emerged from research that has often examined the pedagogical side of public EFL education. However, there is also a growing body of research that has centered on the experience of EFL learning in secondary school education.

In this respect, the studies have explored what students think or feel about their EFL learning. For instance, Lara (2015) examined Mexican secondary students’ perceptions about learning English through content. The data revealed that students initially had negative perceptions about using the language, but later they felt comfortable learning English through content. This study revealed that suitable EFL materials and innovative teaching strategies need to be considered to motivate learners. Méndez-López (2022) conducted a quantitative study to also identify emotions in a Mexican public secondary school in Mexico. She identified that female students held positive emotions, whereas male students felt less comfortable to show their emotions in the EFL class.

The latter studies bring about an important aspect that has been missing in the exploration of EFL learning in the Mexican context. Probably, this aspect has received little attention as English instruction is delivered in a top-down manner. In this regard, EFL teachers follow the guidelines found in the national plans created by the Minister of Education of Mexico (SEP, 2018). Nonetheless, attention needs to be paid to learner’s perceptions regarding the learning of English (OECD, 2013). To fill this gap, this study explores the perceptions of public secondary school students about the teaching of EFL in the Southeast of Mexico.

Learners’ perceptions of EFL learning

EFL learner perceptions are important in the educational field. Wright (2004) affirms that perceptions vary among individuals and people perceive different things about the same situation. Vásquez-Guarnizo et al. (2020) state that people assign different meanings to what they perceive, and the meanings given to a situation might change accordingly. Moreover, the authors define perceptions as personal interpretations of information from everyone’s own reality in which students pay attention to a particular situation, experience, or action to reflect the way they view the world. Scientific studies have explored perceptions of EFL learning. In these studies, “perceptions” refer to language orientations, which help to situate the participants in terms of how they perceive the English language learning. These language orientations are related to the study of language learning where motivation and attitudes can be associated with perceptions. They are dimensions that have been included to define positive or negative perceptions that students have about EFL learning (Guilloteaux, 2007). Motivation and attitudes exert an influential power on students’ positive or negative perceptions of EFL learning (Lasagabaster & Doiz, 2016).

In the international context, some studies have tapped into learners’ perceptions of the instruction they receive in higher education for EFL education. Almusharraf (2020), for instance, conducted a study in Saudi Arabia in which EFL students expressed their perceptions of learning English. The author contributed to defining the perceptions by remarking that students could change or confirm their perceptions while they can be positive or negative, and that perceptions describe how learners engage in critical self-reflection. There is also a study from Huh et al. (2022) conducted in China and Korea in which they explored perceptions in EFL students. The results indicated that students positively perceived face-to-face English learning for communicative competences in language learning. Dhanarattigannon and Thienpermpool (2022) also evaluated the perceptions of EFL students in Thailand. They classified perceptions into levels of agreement that were positive or negative and evaluated them through a questionnaire in which the dimensions explored were as follows: content, organization, vocabulary, language use, mechanics, overall confidence, and attitude toward revising essays. The results of this study revealed that students had a positive perception about self-assessment as a tool for practicing their writing development, and they exhibited positive attitudes and self-confidence in writing.

Cancino and Towle (2022) affirm that is necessary to pay attention to students’ perceptions, as they can provide valuable feedback that could help educators design EFL courses for students. The authors conducted a study with EFL students in Chile using Likert scale questionnaires. The findings revealed a significant relationship between computer self-efficacy and perception toward fully online language learning components. The perceptions that learners held toward fully online courses appeared to be unaffected by gender and proficiency level. In a different study, aimed at evaluating perceptions in EFL students, Bardianing and Yudi (2020) also utilized Likert scale questionnaires in Indonesia with positive or negative agreement answer choices. The findings of this study showed that most of the students had positive perceptions of each element of the Rhetorical Précis when making summaries of original texts.

There is evidence, however, that learner perceptions may vary depending on their proficiency (Alotaibi, 2022; Tsai, 2021; Wu, 2022). To define EFL proficiency, Arisman (2020) stipulates that language proficiency refers to the extent to which a person can use a language in terms of vocabulary, writing, reading, speaking and communicative skills. The importance of classifying students into different proficiency levels to evaluate their perceptions is evident in various studies. Tai and Chen (2021) conducted a study with Chinese university students who were classified into low or high proficiency levels. The study highlighted the significance of classifying EFL learners based on proficiency levels and exploring strategies that can be used in the classroom. This study found that the high proficiency level students exhibited more positive perceptions and better performance in different tasks. To contribute to these types of studies, Ünal et al. (2017) examined the relationship between university EFL learners’ perceptions and EFL proficiency level in Turkey. EFL proficiency was measured with a proficiency test, which underwent reliability analysis. The study found significant differences in the constructs of technical perspectives on learner autonomy, benefits of learner autonomy to language learning, and the role of the teacher in promoting autonomy and proficiency. However, the data indicated that there was not a significant difference between learner’s perception and their proficiency levels.

The studies were conducted with higher education students in different contexts worldwide. In lower educational levels, the limited number of studies conducted thus far indicates that different aspects of the language learning experience can influence learners’ perceptions of EFL education in secondary and elementary settings where English has become a compulsory subject. These studies have also revealed that learner perceptions can be influenced by factors such as ethnicities, medium of instruction, and mother tongue (Mäkipää & King, 2021). For example, in elementary education, Salim and Hanif (2020) found that learners in Indonesia with access to adequate English language learning resources held positive perceptions about their English learning experience.

In secondary school education, Quadir (2021) found that learners’ perceptions were influenced by their demotivation to study English as a school subject in Bangladesh (see also Imsa-Ard, 2020). In Jakarta, Depok, and Bekasi, Pardede (2020) conducted a study to explore secondary school learner perceptions and the use of ICT (Information and Communication Technology) in the EFL classroom. The results showed that the participants’ perception was positive and high in some dimensions of ICT use in learning: potentials of ICT use to increase learning interest and motivation; the impacts of ICT in learning; educational values and ICT use self-efficacy. In Norway, Normann (2021) examined a group of upper secondary students’ reflections around their own language-learning experiences in three project mobilities they had in EFL class. Students’ perceptions were positive because they had opportunities for learner-learner interaction with other non-native speakers of English. Cheng and Tsang (2021) conducted a study with secondary school students in Hong Kong. The learners were classified in high or low proficiency levels. The results pointed out that learners with high proficiency levels performed better in different tasks and held more positive perceptions in comparison to low proficiency level students.

These studies reveal that there is a growing interest in examining learners’ perceptions of EFL education. Nonetheless, the research also shows that this issue has mostly been explored in the higher education context. The small quantity of studies at elementary and secondary school levels substantiates different aspects of the learning context which can have an influence on the learners’ perceptions. In addition to the aspects of language classroom experience, proficiency seems to also contribute to the type of perceptions learners hold about EFL education. Nonetheless, this issue has received little direct attention in Mexico. Thereafter, in this descriptive study, the role of language proficiency of the students and their perceptions of public EFL education are examined together, as recommended in previous research (Cheng & Tsang, 2021).

Public EFL educational policies in Mexico: The top-down approach

EFL education in Mexico is sanctioned using a top-down approach, because the guidelines for basic education are centralized and set by the Minister of Education (e.g., SEP, 2017a, 2017b, 2022). This characteristic of the national guidelines’ establishment is congruent with Sabatier’s (1986) definition of the top-down approach to educational policy establishment. In this approach, the educational guidelines derive from centralized policy decisions which sanction the goals that need to attain over time. Conversely, a bottom-up approach starts by involving the actors involved in service delivery in local areas and makes them feel part of policy establishment by considering their opinions, goals, activities, strategies, etc.

Extensive empirical evidence from the urban and rural settings of Mexico instantiates the top-down approach. Moreover, when teachers are consulted, these consultations tend to focus on the validation of the centralized policies, as the work of Izquierdo and his colleagues have systematically indicated (see Hernández & Izquierdo, 2023; Izquierdo et al., 2021, 2017, 2016). The top-down approach to EFL public education has affected teachers and students as key actors in education. An example of the centralized enactment of the EFL curriculum is the program PRONI with its acronym in Spanish. This program aimed to modify teachers’ practices through training, certifications, and different technological resources (PRONI, 2022, 2023). Nonetheless, this program did not reach all teachers in public schools (Hernández & Izquierdo, 2023, 2020). In this regard, Hernández and Izquierdo (2023, 2020) demonstrated, through quantitative and qualitative data, that teachers’ perceptions were negative towards the centralized EFL reforms (see also Izquierdo et al., 2021). Teachers have often complained that the training programs and curriculum were far from being sensitive to the realities of the learning contexts and conditions of learners in urban and rural areas. It is within this context, that the current study aims to examine the perceptions that young secondary school learners from different proficiency levels have regarding English language learning in the Southeast of Mexico. Subsequently, two research questions were addressed.

- What kind of perceptions do public secondary school learners hold about their EFL learning experience?

- How does their EFL proficiency affect their perceptions?

Method

Research Design

To answer these research questions, this quantitative study draws on a descriptive study design. This design enables the collection of numerical data without altering the natural conditions of the students (Cohen et al., 2007). The quantitative data were collected from 114 students in the 2nd grade of a public secondary school located in Southeast Mexico. To assess their English proficiency level, a proficiency test was administered to the sample of students. Their perception data was collected using a survey and a 4-point Likert scale questionnaire (Cohen et al., 2018). Based on the research design, the data was analyzed to identify relationships between the perception and proficiency variables. The following sections provide detail information on the different research components of the study.

Variables

In this study, both an independent and a dependent variable were considered. The independent variable is the level of L2 proficiency of the learners while the dependent variable is their perceptions of EFL learning.

The level of proficiency was determined using an adapted version of an international English proficiency test. The test results were used to classify the secondary school students into two proficiency conditions: low proficiency level and intermediate proficiency level. The dependent variable encompasses the perceptions of the EFL learning experience held by the secondary school learners. Through their answers in a Likert scale questionnaire, the learners indicated how they perceive the process of English language learning in public education.

Context & Participants

The current study was conducted in a public secondary school in the Mexican state of Tabasco. The participating secondary school was selected due to accessibility and the expressed interest of the school administration and teacher in the study. In the selected school, the total number of students enrolled in the morning shift is N= 806 and their age ranged from 13 to 14 years. The students attended regular English classes which are part of the Mexican curriculum within the EFL subject. With this population, non-probabilistic convenience sampling was used (Cohen et al., 2018). The final dataset included responses from N=114 students (62 male, 51 female and 1 other genre) in Grade 2 who consented to participate in the study. The study had the approval of the authorities and teacher from the chosen public Mexican secondary. Ethical and consent forms were handed out to participants and all the people involved in the project signed these forms before taking part in the present study.

Data Collection Instruments

Survey: design, validity, and reliability

Lodico et al. (2006, p. 66) point out that surveys can be used to collect different data types and thereby obtain general information from the participants in a study. The survey had the following sections: section 1. General information, section 2. Background of English language study, section 3. Modalities of English language study and section 4. Background of content-based English study. The type of questions included multiple choice and some closed-ended questions. The instrument was administered in Spanish. The survey was subject to content, ecological, and face validity. Content validity was conducted with three teachers from the secondary school. The ecological and face validity were conducted with 114 participants in different groups from the public secondary school selected. These learners were also in Grade 2 and were different from the final sample.

Validity is how well the tool measures what it aims to measure (Boyle & Fisher, 2007, p. 59). To establish content validity, a group of expert judges evaluated the different sections and questions in the survey. These three expert judges have undergraduate degrees in foreign language teaching and hold language proficiency certificates; one of them has a master’s degree. All of them have more than ten years of EFL teaching experience in public and private elementary and secondary education. They indicated that they were familiar with the use of surveys, proficiency tests and questionnaires in secondary level education, as they have participated in EFL secondary education research projects. The judges first signed consent and approval forms. They were provided with a quantitative matrix in an Excel document to assess and grade the question and section. The following questions were asked: “Is the item consistent?”, “Is the item clear?”, and “Is the item relevant?” If the judges agreed the question met the characteristics, they graded with a 1(yes), whereas if they disagreed or felt the question did not meet the characteristics, they graded with a 2 (no).

Furthermore, the survey underwent ecological validity assessment in which it was administered to different secondary groups. Notes were taken to evaluate if the survey items were clear and consistent, and any items that were found to be unclear or inconsistent were marked.

Face validity was addressed when the instrument determined if it “looks like it is going to measure what it measures”. The students and the teacher completed the survey while the researcher took notes about the performance in the application.

During the pilot stage, after conducting content validity, in section number one, item one was modified in the last word. Instead of saying “Write your current age” it ended up saying “Write your age”. In the item number two, the options were: “a) male” or “b) woman”. Other items were changed too: item 3 and 4 in section 1 and section 2, item 1.

During ecological validity, in the first section, some students mentioned the need to utilize an option C that included: “other”. Most of the students had questions about item 6, they did not understand what socioeconomical status meant.

For face validity, the EFL teacher remarked the importance or excluding item 6 in section 1. Upon completion of the different validity procedures, the survey included four sections with a total of 22 items.

Perception questionnaire: design, validity, and reliability

This instrument consisted of a series of items with 4-point Likert scale (adapted version from Lasagabaster & Doiz, 2016). The scale included two choices for disagreement (i.e., totally disagree, partially disagree) and two choices for agreement (i.e., partially agree, totally agree). The instrument was administered in Spanish. The following sections discuss the different types of validity and reliability procedures conducted with this instrument, including content and ecological validity.

Content validity was assessed by the expert judges that were referred to in the previous sections. The judges participated in a video recorded session where they evaluated the different dimensions and items developed in the questionnaire with the same questions and procedure as the previous section in the survey.

For ecological validity, the questionnaire was administered to 114 voluntary learners who provided their opinions about the relevance of the questionnaire items. Throughout the process, ethical principles and consent guidelines were followed, consistent with the other instruments used in this research (Cohen et al., 2018).

Boyle and Fisher (2007) and Cohen et al. (2007) emphasize that reliability involves assessing the consistency and accuracy in the data collected through an instrument. Various authors suggest that reliability entails evaluating the consistency and stability of the data obtained from questionnaire items (Cohen et al., 2007; Field, 2013). Reliability can be examined at different levels, including stability, equivalence, and internal consistency. Internal consistency is typically assessed using measures such as Cronbach’s Alpha or Coefficient Alpha (Cohen et al., 2018). In this study, the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was calculated using the statistical software SPSS v.25. The coefficient was evaluated for each dimension of the questionnaire, and a reliability threshold of .70 or higher was considered acceptable.

During the pilot stage, for content validity, the expert judges made comments and adjustments in the items. The first item was modified: “Practice grammar should be important in English class. Example: learn the present simple or other grammar tense”. Several items were modified too: 2 to 15 items.

As ecological validity was checked, most of the students did not understand what the word “grammar” meant in the first item. Many students had doubts regarding items 10 and 14.

During the reliability analyses, dimension 1, Perceptions regarding the practice of English skills, items were analyzed and tested by Cronbach´s Alpha. The alpha obtained was satisfactory (α= 0.70), as the test results yielded favorable internal consistency in this section. Therefore, this section included 7 items as part of dimension 2. For perceptions regarding the English class, the alpha obtained was below the level of acceptance (α= 0.28); thus, these results were not considered favorable, and the complete dimension was excluded in further analyses. In the dimension 3, self-efficacy in English learning, the alpha obtained was satisfactory (α= 0.83), and the test results yielded favorable internal consistency in this dimension.

To sum up, after the validity and reliability procedures, the questionnaire included only two sections: Perceptions regarding the practice of English skills and self-efficacy in learning English. The former had seven items and the latter six. In total, the questionnaire had 13 items.

Test: design, validity, and reliability

The test aimed to measure the English language proficiency level of secondary learners based on a global score. The global scores were used to categorize students into two proficiency conditions: low proficiency level or intermediate proficiency level. The test was adapted from a standardized A2 Key level test from Cambridge (Cambridge, 2020). The initial version of this test included the following sections: listening, speaking, writing and use of English. The original version comprised open questions, writing spaces for student responses, and multiple-choice questions. An answer key was provided for the multiple-choice questions, and the test had a duration of 110 minutes. However, for the purpose of this research conducted in a secondary setting, the original version required adaptation.

During the adaptation process, several modifications were made to the test. Two versions of the test were created for reliability purposes. The reading comprehension section in version 1 had 1-18 questions, while in version 2 it had 13-30 questions. The use of English section in version 1 had 19-30 questions, whereas in version 2 it had 1-12 questions. All question instructions were presented in Spanish, and for each test question the students were given multiple choices to select from. The total number of items across these sections added up to 30. This version underwent content and face validity checks, as well as reliability procedures to ensure the stability of answers.

Content validity was established by making professional judgements regarding the relevance of the test prompts (Cohen et al., 2018). For this research, the adapted version of the test was reviewed by the three expert judges who were referred to in the previous sections. Moreover, a new judge participated in the validity and reliability analysis phases. This judge is a quantitative research specialist who holds a PhD in Second Language Education and has conducted research on the learning of foreign languages in Mexico and abroad. The researcher has published in top-tier national and international second language education journals. The experts engaged in discussions to determine the sections of the test that were suitable for inclusion in the study. They assessed the appropriateness and relevance of the test questions for measuring the proficiency of secondary school learners.

Afterwards, face validity was checked by piloting the test in different secondary groups and having the test checked by their respective English teachers once again. Following the test administration, some students provided their feedback on the instrument, and the researcher took notes regarding the administration process and participants’ opinions. The procedures adhered to ethical and consent principles (Cohen et al., 2018), and the maximum duration of the test was one hour.

To ensure reliability, the stability of the learners’ answers was verified (Cohen et al., 2018). As such, two versions (1 and 2) of the test were administered. Both versions included the same prompts, but the order of the sections altered between the versions. The test administration was organized to ensure an equal distribution of the versions across classrooms.

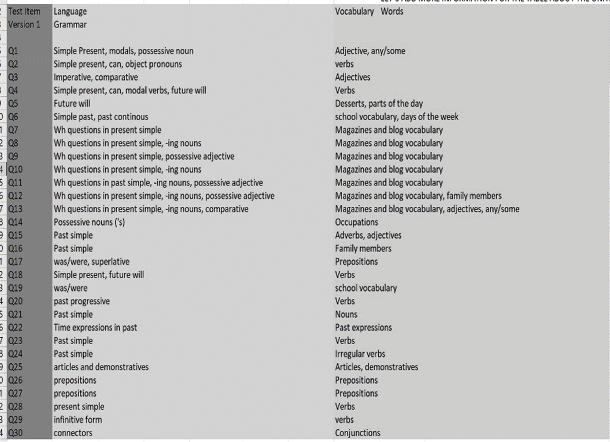

During the verification of content validity, the experts considered that it was necessary to keep the reading and writing sections, but with some adjustments in the writing section. Throughout these discussions, the grammar, content, and vocabulary found in the test were identified and recorded in a chart (See Figure).

Figure. Grammar, content, and vocabulary Identified by experts in the adapted version.

During face validity, the EFL teacher from the secondary school mentioned that the test was suitable for the learners. He considered that the level of difficulty was not a problem; however, the students considered that the level of difficulty was high and challenging for them.

To verify reliability between test versions, first, the normality test was run separately per version (1 or 2). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov yielded a significant result for version 1 and version 2. Therefore, the scores were not normally distributed in either version. In the absence of a normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney analyses for unrelated samples were used to check the stability of answers between test versions. The global results confirmed that global scores did not differ significantly between versions.

Results

Survey Results

The survey collected sociodemographic information and background of the participants in this study. The analyses focused on the frequencies of answers to interpret the different sections and questions presented to the secondary learners. The first results were the following ones:

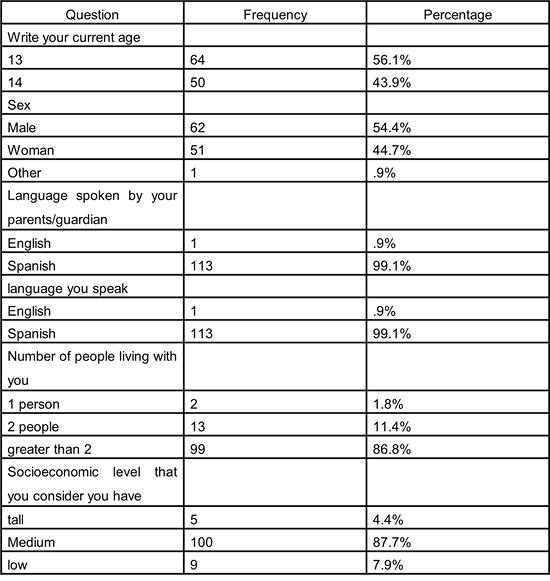

The frequency analyses revealed that most students’ age was around 13 years old (56.1%). The preponderant genre in students is male (54.4%). Nearly all students spoke Spanish (99.1%) only one student reported that one of their parents had high proficiency in English. Most of the students live with more than two family members (86.8%) and the socioeconomic level that students consider having is medium (87.7%) (see Appendix Table 1).

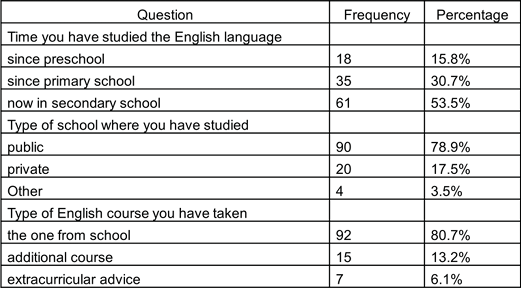

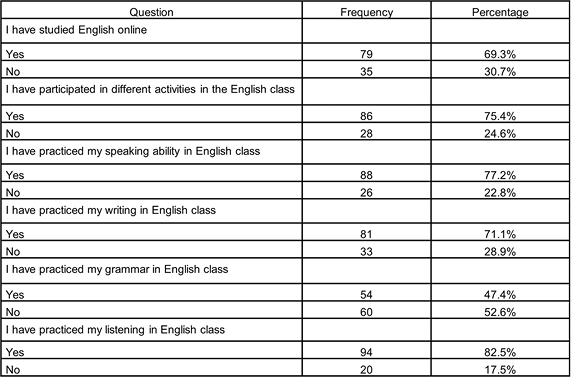

The frequency analyses reported that most of the students had studied English until secondary school (53.5%). Most of the students had only studied in public schools (78.9%) and most of the students had studied English only with the regular English classes at school (80.7%) (see Appendix Tables 2 and 3).

Based on the results obtained, most of the students had studied English in an online modality due to the pandemic and participated in EFL classes. A surprising fact is to see that most of EFL students reported having practiced speaking, writing, and listening in their classes and a few students indicated to have practiced grammar in EFL class (see Appendix Table 4).

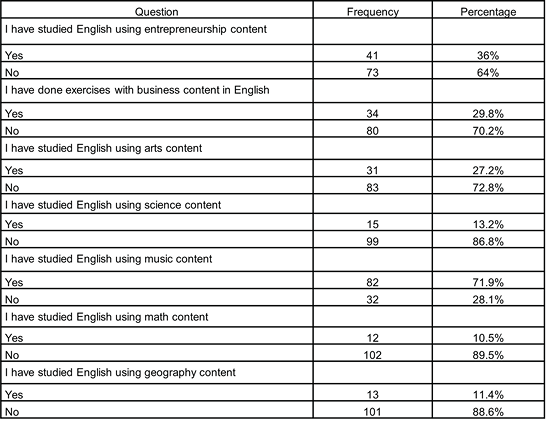

Proficiency Test: Global Scores & Proficiency Grouping

The results obtained from the 30 test questions revealed the following proficiency results. First, the population mean, and standard deviation were computed to start the process of proficiency grouping using Z-Scores.

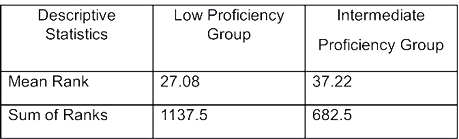

Using the Z-scores, the participants were divided into Low proficiency and Intermediate proficiency. The classification was the following one: If the participant obtained a -1 z-score or below, the participant was classified as Low proficiency (n = 42); and if the participant obtained a 1 z-score or above, the participant was classified as Intermediate proficiency (n = 18) (see Appendix Table 5).

Due to the absence of normality in the results, non-parametric analyses were conducted to identify the differences between both groups. The Mann-Whitney analysis confirmed the differences between both proficiency groups of learners. The next section covers the results obtained in the EFL Perception Questionnaire applied to the learners.

Perception Questionnaire: Results

Regarding section 1 of the EFL perception questionnaire, this section incorporated items 1 to 7 and explored perceptions regarding the practice of English Skills. The results obtained in the item 1: English grammar should be important in English class yielded a positive skewed perception among the whole participants. The same situation happened with the items that explored English reading importance in EFL class (item 2), English writing (item 3), vocabulary in English class (item 4), pronunciation (item 5), listening (item 6) and speaking (item 7).

Regarding section 3 of the same instrument, this dimension incorporated the self-efficacy in learning English to items 17-22 in which the results obtained were: Item 17 was: I have improved my reading in my English class, 51% of the students partially agree, which could reveal that half of the group yielded a positive perception and half of the group a negative perception. The same happened with item 18 when the students were asked if they had improved their ability to speak in their English class, 41.2% yielded a partially agreement. In item 19, 34.2% of the students yielded negative perception and 36.8% a positive perception. In the case of the perception in item 20 about if the student perceived to have improved his or her own listening comprehension, 48.2% of students partially agree. The same partially agreement happened with vocabulary and grammar in the final two items with a similarity in 44% of students.

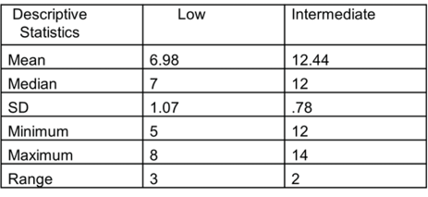

Dimension 1: Comparison between Proficiency Groups

The results from the EFL Perception Questionnaire and the EFL Proficiency Test served to determine if there was a relationship between the proficiency level that the student has and his or her perceptions. The dimension 1 included items to explore perceptions regarding the practice of English skills and the descriptive statistics obtained in the participants are presented in Appendix Table 6.

Non-parametric analyses were conducted to verify if there were differences between the proficiency groups. Mann-Whitney test results confirmed that there were no differences between the low and intermediate proficiency learners regarding the practice of English skills. All group learners yielded the same perception of the practice of writing, vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar, listening and speaking. There was no relationship between their proficiency level and their perceptions in this section.

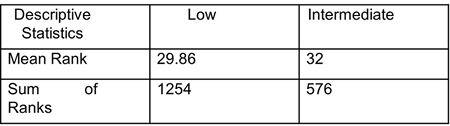

Dimension 3: Comparison between Proficiency Groups

The comparisons between the EFL Perception Questionnaire and the EFL Proficiency Test were run in dimension 3. Self-Efficacy in Learning English. This was done to evaluate if there was an effect between this dimension and the EFL proficiency that the learners have. The results obtained are in Appendix Table 7.

The non-parametric analysis Mann-Whitney U was conducted to verify differences between proficiency level of the student and results obtained in the EFL Perception Questionnaire. The results indicated that there were differences between low and intermediate proficiency group learners in their perceptions of self-efficacy in learning EFL.

Discussion

There is a need to conduct research in secondary education settings and collect data to understand the perceptions of EFL learners. Additionally, EFL education is still delivered using a top-down center approach (SEP, 2020) and it requires further attention to understand what students at the basic educational levels in public educations perceive about their EFL classrooms. The research questions in this study were to identify how the L2 proficiency of public education learners affected their perceptions about EFL learning. The first research question addressed what kind of perceptions public secondary learners hold about their EFL learning. The adapted version of the questionnaire (Lasagabaster & Doiz, 2016) was submitted to validity and reliability procedures to gather a final version of an instrument to obtain reliable and generalizable data about EFL learners’ perceptions. The EFL perceptions questionnaire was modified by following the principles of quantitative research on its elaboration (Cohen et al., 2018). This instrument focused on exploring the construct of EFL perceptions among secondary learners, earners, as addressed in various theories (Guilloteaux, 2007; Vázquez-Guarnizo et al., 2020; Wright, 2004).

The administration of this instrument provided relevant findings for EFL research, as it prioritizes the participation of EFL learners in expressing their perceptions about their learning experiences and instruction received. For example, in the research conducted in China and Korea by Hu et al. (2022), it was found that EFL learners positively perceive practicing speaking in class and this finding contributed to evaluate the importance of EFL skills in class. This finding was corroborated by the positive perceptions expressed by the EFL secondary students in this research regarding the practice of various EFL skills. The quantitative results show that EFL learners from both low and intermediate proficiency levels had a positive perception about the importance of the integration of vocabulary, speaking, writing, reading, and listening in the EFL classes. These findings align with the results of studies by Ünal et al. (2017) in Turkey and Salim and Hanif in Indonesia (2020), which suggested that there were no differences in the perceptions of EFL learning based on students’ proficiency levels. They also emphasize the significance of practicing different skills in EFL classes and how learners from different proficiency levels hold positive perceptions when these skills are integrated into teaching and learning.

One contribution of this quantitative questionnaire is its applicability in various settings, not limited to EFL secondary learners in similar contexts. It can be administered across different levels and educational contexts. Several studies conducted worldwide have aimed to explore EFL learners’ perceptions, such as in elementary education in Indonesia (Salim & Hanif, 2020), secondary education in Bangladesh (Quadir, 2021), secondary schools in Kakarta, Depok, and Bekasi (Pardede, 2020), upper secondary learners in Norway (Normann, 2021), and secondary learners in Hong Kong (Cheng & Tsang, 2021). This research, along with further research globally, can benefit from the use of EFL perception questionnaires that follow quantitative research principles and validity and reliability procedures to obtain generalizable data from EFL students.

Regarding dimension 1: Perceptions towards the practice of EFL skills, all students held similar perceptions regarding what they need to practice and how things should be taught (including grammar, reading, writing, vocabulary, and pronunciation). This finding is consistent with the results from Arisman (2020), which suggests that language proficiency is linked to the idea of performing in vocabulary, reading, writing, speaking and different EFL skills, and that EFL learners require interaction in class to develop positive perceptions about the teaching received, thereby increasing their interest and motivation. These results present a challenge for EFL classes when EFL learners demand the incorporation of these language elements into daily teaching practice and learning. However, EFL teachers need to adhere to the curriculum in accordance with the educational level and work with the available sources they have in their schools (Vázquez-Guarnizo, 2020). This constitutes a major challenge for EFL teachers when they attempt to meet students’ expectations and incorporate top-down approaches to EFL teaching. Moreover, the secondary curriculum in Mexico does not consider students’ perceptions of EFL learning and teaching, designing guidelines and expected outcomes. It is designed in a top-down manner (SEP, 2018, 2017a, 2017b).

The recent curriculums (SEP, 2023, 2022) need to reconsider the importance of EFL learning in basic education at secondary level. These guidelines have a significant impact on EFL classes, teaching, and learning hindering the incorporations of further improvements in EFL skills practice for secondary learners in Mexico. For example, the fact that students’ interests should be considered in the reality of the students in EFL classrooms and the importance of developing professional competencies in EFL teachers to enhance their practice to promote the transversality of the curriculum and the social function of the English language in secondary education (Izquierdo et al., 2014). Observations of EFL teaching practices indicate that language teaching is structured based, because there is no integration of cultural aspects and no integration of other relevant aspects of the curriculum. Another example could be seen in Izquierdo et al. (2016), in which teachers alternate between English and Spanish in the classroom. Izquierdo’s analysis of the classroom language indicate that Spanish is used for communicative purposes, whereas English is used to explain grammar rules. Thereafter, the use of English in the classroom remains far from being the means of communication. Instead, English remains the object of study. These challenges in incorporating EFL for communicative purposes in EFL classrooms are consistent with curriculum problems found in research in various countries: Israel (Awayed‐Bishara, 2021), Saudi Arabia (Elyas & Badawood, 2017) and South Korea (Yang & Jang, 2020).

In the EFL perception questionnaire, dimension 3 focused on self-efficacy in EFL learning. The results showed that proficiency level has an impact on how students perceive their improvement and achievements through public education. Some students perceived they had improved the language system such as grammar and vocabulary, as well as in the skills of reading, speaking, writing, and listening. On the other hand, some students expressed more negative perceptions regarding their improvements in EFL skills. These differences were identified when students were classified in two EFL proficiency levels: low and intermediate. This dimension also answered research question 2 which investigated the influence of L2 proficiency on students’ perceptions. Regarding research question 2, these dimensions explored how EFL learners perceived EFL classes and their self-efficacy in EFL learning. The quantitative results showed that learners with a higher proficiency level exhibited more positive perceptions of having acquired various EFL skills compared to students with a lower proficiency level. The questionnaire data indicated that proficiency level plays an important role in the perceptions of EFL learning among students. This data allowed to see proficiency as an important element in EFL education that has an impact on EFL learners’ perceptions. This finding aligns with previous studies that examined the relationship between perceptions, EFL proficiency, and their impact on students’ positive or negative perceptions (Almusharraf, 2021; Cancino & Towle, 2022; Dhanarattigannon & Thienpermpool, 2022).

These studies highlight the importance of self-efficacy in EFL learning and how it can be affected by different proficiency levels. These factors can be further explored and interconnected in future research, incorporating, quantitative instruments to examine EFL learners’ perceptions in different contexts. One strength of this research lies in the inclusion of the self-efficacy dimension measuring EFL learners’ perception. This finding can be compared to the findings of AlAdwani and AlFadley (2022) in Kuwait, who discovered that perceptions could differ in terms of learners’ self-assessment of their ability to learn and attain EFL skills.

The data provided us with insights into the significance of proficiency and perceptions when exploring self-efficacy in EFL learners. Our results are congruent with previous evidence suggesting that these perceptions may vary depending on the learners’ proficiency levels, as indicated by studies that examined both elements together and obtained similar results (Alotaibi, 2022; Tsai, 2021; Wu, 2022).

One limitation in our research was the absence of dimension 2: Perceptions about the EFL class, which could have provided additional information to contribute to this study. This dimension was eliminated due to the lack of reliable results obtained in the Cronbach Alpha analysis. Consequently, questions remain regarding the perceptions that learners at different proficiency levels hold about the classroom activities, materials, and performance. In the Mexican public secondary school context, there is published observational research on what teachers do in the classroom (Hernández & Izquierdo, 2020; Izquierdo et al., 2021; Izquierdo et al., 2020). Nonetheless, there is a need to explore what students think about what the teacher does in the classroom, how they feel about what they are requested to do, the materials they use, and the role they take in the classroom.

Another limitation relies on the use of statistical data only. Further studies could benefit from a mixed method or qualitative approaches too. There is a limitation in using just one research design in a study, because there has been research conducted for EFL public secondary level in Mexico in which the integration of mixed method or qualitative approaches, have provided a more holistic view of the challenges of EFL education in secondary education. For example, Hernández and Izquierdo (2023) conducted a study with rural secondary school teachers in Mexico with a mixed method, obtaining low levels of teaching satisfaction with respect to the integration of the EFL practices indicated in the national curriculum in the regular classes. Due to their research design, the researchers were able to explain the results building upon the explanations and critiques provided during teacher interviews. Another study that also provides a holistic view of the challenges of EFL education is the one conducted by Izquierdo et al. (2017). The authors conducted a study with secondary teachers in Mexico by using a quantitative and qualitative component to examine their perceptions on EFL teaching with technological resources. The quantitative and qualitative results obtained supported the idea that there is a need to improve teaching practices, resources, training, and engagement with national reforms. Considering the benefits of mixed-methods research, through a qualitative component, we will be able to further expand, covering the limitations of just using questionnaires or statistical data.

Teachers as key actors in education have implications on their professional development to enhance students’ learning, even though they have put efforts to teach EFL without sustainable training (Izquierdo et al., 2021). Moreover, it is important to reduce language breakdowns and promote a more effective use of EFL for communicative purposes. This requires moving away from using EFL to teach grammar rules or to translate English lessons. Teacher’s professional development is a factor that can contribute to this end and requires further attention to help teacher improve teacher-students interaction as a key component of EFL holistic learning. Moreover, training needs to contribute to improve teaching strategies for EFL teachers in secondary schools in Mexico (Izquierdo et al., 2016, 2021; Jaime et al., 2021).

In future research, there is a need for reliable instruments that allow collecting generalizable data from young learners. Even though there is research conducted in higher education to evaluate EFL students’ perceptions (Akbarnezhad et al., 2019; Bao, 2019; Zhiying, 2018), there is still a need to conduct more studies in public secondary education using reliable quantitative instruments. This research is particularly relevant in the Mexican context, where all secondary school students are compelled to learn English in public education. These concerns can be investigated in further research using quantitative research instruments that allow obtaining reliable information about what teachers perceive in EFL classrooms, how they perceive their teaching, and how they can participate in improving teaching and learning. Moreover, the need to obtain information from EFL learners to improve teaching and learning can be investigated using questionnaires that meet validity and reliability procedures of quantitative research (Cohen et al., 2018, 2007). This study provides some valuable information about EFL research and the need to conduct research that includes teachers’ and students’ perceptions, which could help educational researchers improve instructional practices in EFL settings and obtain generalizable data or reliable instruments that can be replicated in public education.

The evidence in this current study opens a research line to investigate and conduct more research with instruments that can allow the researchers and stakeholders to obtain reliable information about students in public education in an EFL setting. An interesting element in this study, is the importance of incorporating research that pays attention to the learner and the perceptions they hold in an EFL context. This information can help educational actors make decisions about different elements that are part of EFL instruction and EFL settings. Finally, while the research questions were answered, some modifications in dimension 2 could have helped collect more data. However, the instruments created and adapted in this research, following quantitative principles, formulate an interesting opportunity to be replicated in different EFL settings to obtain sociodemographic information, EFL perceptions and EFL proficiency level in EFL secondary learners.

Conclusions

EFL learners’ perceptions constitute a topic of major concern in EFL research when they can be explored along EFL proficiency levels (Zulkefly & Razali, 2019). When examined together, perceptions can vary depending on the students’ proficiency level. However, curriculum policies seem to have largely ignored the input of stakeholders in education when designing EFL programs for teaching and learning (SEP, 2022, 2017a, 2017b), despite students being the target audience of these programs. This is the main concern of paying attention to EFL learners’ perceptions of their EFL learning (Bao, 2019).

The quantitative data obtained reveals that EFL students from different proficiency levels value the practice of different EFL skills in EFL learning (writing, grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, listening, and speaking). However, EFL students with a higher proficiency level yielded more positive perceptions of their self-efficacy improving these skills compared to those with lower proficiency levels, who display more negative perceptions regarding their self-efficacy in EFL learning. These findings contrast with studies conducted on higher education students, which showed differences based on EFL proficiency levels Akbarnezhad et al. (2019) and Zhiying (2018). The population in this study implicitly perceives that there is room for improvement in EFL classes to foster more positive perceptions of skill improvement and better learning outcomes. EFL research conducted in public education in Mexico emphasizes the need for improvement in EFL classes enhance EFL teaching and learning (Izquierdo et al., 2021; Hernández & Izquierdo, 2020; Izquierdo et al., 2020). There is a small number of public secondary studies that explore EFL perceptions with L2 proficiency level with reliable instruments to obtain generalizable information in these settings. This article contributes to the use of quantitative instruments to give a voice to students’ perceptions in EFL public education. Furthermore, it explores research conducted worldwide on EFL perceptions and L2 proficiency as important elements that require further attention to improve EFL teaching practices and EFL learning. Instruments developed and adapted can be applied in different settings in EFL educations. This research also addresses an existing gap in EFL research, both in Mexico and globally, which has primarily focused on higher education settings, neglecting the perspective of EFL secondary learners in public educations.

Akbarnezhad, S., Sadighi, F. & Sadegh, M. (2019). Iranian EFL learners’ perception of the English verbs’ argument structure and their language proficiency: A semantic-syntactic approach. Cogent Education, vol. 6, núm. 1, pp. 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1674576

AlAdwani, A. & AlFadley, A. (2022). Online learning via Microsoft TEAMS during Covid-19 pandemic as perceived by Kuwaiti EFL learners. Journal of Education and Learning, vol. 11, núm. 1, pp. 132-146. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v11n1p132

Almusharraf, N. (2021). Perceptions and application of learner autonomy for vocabulary development in Saudi EFL classrooms. International Journal of Education and Practice, vol. 9, núm. 1, pp. 13-36. https://archive.conscientiabeam.com/index.php/61/article/view/688/1000

Alotaibi, A. (2022). Voicing contrast of L2 final stops: A case study on ESL learners from Saudi. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, vol.18, núm. 2, pp. 1194-1207. https://www.jlls.org/index.php/jlls/article/view/3227/1088

Arisman, R. (2020). The relationship between direct language learning strategies and English learning proficiency at senior high school students. J-SHMIC: Journal of English for Academic, vol. 7, núm. 2, pp. 41-51. https://journal.uir.ac.id/index.php/jshmic/article/view/5339/2679

Awayed-Bishara, M. (2021). Linguistic citizenship in the EFL classroom: granting the local a voice through English. TESOL Quarterly, vol. 0, núm. 0, pp. 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3009

Bao, G. (2019). Comparing input and output tasks in EFL learners’ vocabulary acquisition. TESOL International Journal, vol. 14, núm. 1, pp. 1-12. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1244083.pdf

Bardianing, W. & Yudi, B. (2020). EFL students’ perception on the use of “rhetorical précis” as a summarizing template. Indonesian Journal of English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics, vol. 5, núm. 1, pp 109-120. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1281547.pdf

Boyle, J. & Fisher, S. (2007). Educational testing: A competence-based approach. Wiley-Blackwell.

Cambridge (2020). A2 key preparation. https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/exams-and-tests/key/preparation/

Cancino, M. & Towle, K. (2022). Relationships among higher education EFL student perceptions toward fully online language learning and computer self-efficacy, age, gender, and proficiency level in emergency remote teaching settings. Higher Learning Research Communications, vol. 12, núm. 0, pp. 25-45. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1317&context=hlrc

Charles, H. & Torres, A. (2022). Dominio del inglés y salario en México. Análisis Económico, vol. 37, núm. 94, pp. 167-180. https://doi.org/10.24275/uam/azc/dcsh/ae/2022v37n94/charles

Cheng, A. & Tsang, A. (2021). Use and understanding of connectives: an embedded case study of ESL learners of different proficiency levels. Language Awareness, vol. 31, núm. 2, pp. 155-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2021.1871912

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education (6th ed.). Routledge.

Dhanarattigannon, J. & Thienpermpool, P. (2022). EFL tertiary learners’ perceptions of self- assessment on writing in English. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network, vol. 15, núm. 2, pp. 521-545. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1358688.pdf

EF English Proficiency Index (2022). The world’s largest ranking of countries and regions by English skills. EF. https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/

EF English Proficiency Index (2021). A Ranking of 112 Countries and Regions by English Skills. EF. https://www.ef.com/assetscdn/WIBIwq6RdJvcD9bc8RMd/cefcom-epi-site/reports/2021/ef-epi-2021-english.pdf

Elyas, T. & Badawood, O. (2016). English language educational policy in Saudi Arabia post 21st century: Enacted curriculum, identity, and modernisation: A critical discourse analysis approach. FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education, vol. 3, núm. 3, pp. 70-81. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/fire/vol3/iss3/3

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using SPSS (2nd ed). Sage Publications.

González, A. (2009). On alternative and additional certifications in English language teaching: The case of Colombian EFL teachers’ professional development. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, vol. 14, núm. 22, pp. 183-209. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.2638

González, R., Vivaldo, J. & Castillo, A. (2004). Competencia lingüística en inglés de estudiantes de primer ingreso a instituciones de educación superior. Unidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Iztapalapa-México.

Guilloteaux, M. (2007). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of teachers’ motivational practices and students’ motivation Doctoral thesis, University of Nottingham.

Hernández, M. & Izquierdo, J. (2023). Teachers’ perceptions and appropriation of EFL educational reforms: Insights from generalist teachers teaching English in Mexican rural schools. Education Sciences, vol. 13, núm. 5, pp. 1-24. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050482

Hernández, M. & Izquierdo, J. (2020). Cambios curriculares y enseñanza del inglés: cuestionario de percepción docente. Sinéctica, Revista Electrónica de Eduación, núm. 54, pp. 1-22. https://sinectica.iteso.mx/index.php/SINECTICA/article/view/1042/1292

Huh, S., Shen, X., Wang, D. & Lee, K. (2022). Korean and Chinese university EFL learners’ perceptions of and attitudes toward online and face-to-face lectures during COVID-19. English Teaching, vol. 77, núm. 1, pp. 67-92. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.77.1.202203.67

Imsa-Ard, P. (2020). Motivation and attitudes towards English language learning in Thailand: A large-scale survey of secondary school students. rEFLections, vol. 27, núm. 2, pp. 140-161. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1283491.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) (2019). Visitantes por entidad de registro según lenguas e idiomas que habla, serie anual de 2016 a 2022. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/tabulados/interactivos/?pxq=f7d47f2c-66bb-4f81-9ca1-424402f30bf2

Izquierdo, J., Aquino, S. & García, V. (2021). Foreign language education in rural schools: Struggles and initiatives among generalist teachers teaching English in Mexico. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, vol. 11, núm. 1, pp. 133-156. https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/ssllt/article/view/22174/25072

Izquierdo, J., De La Cruz, V., Aquino, S., Sandoval, M. & García, V. (2017). Teachers’ use of ICTs in public language education: Evidence from second language secondary-school classrooms. Comunicar, vol. 25, núm. 50, pp. 33-41. https://doi.org/10.3916/C50-2017-03

Izquierdo, J., García, V., Garza, M. & Aquino, S. (2016). First and target language use in public language education for young learners: Longitudinal evidence from Mexican secondary-school classrooms. System, vol. 61, pp. 20-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.07.006

Izquierdo, J., Aquino, S., García, V. & Garza, M. (2014). Prácticas y competencias docentes de los profesores de inglés: diagnóstico en secundarias públicas de Tabasco. Sinéctica, Revista Electrónica de Educación, vol. 42, núm. 42, pp. 1-25. http://www.sinectica.iteso.mx/articulo/?id=42_practicas_y_competencias_docentes_de_los_profesores_de_ingles_diagnostico_en_secundarias_publicas_de_tabasco

Jaime, B., Castillejos, W. & Reyes, A. (2021). Intencionalidades y resistencias en el aprendizaje del inglés: referentes para diseñar estrategias didácticas efectivas. IE Revista de Investigación Educativa de la REDIECH, vol. 12, pp. 1-12. https://www.rediech.org/ojs/2017/index.php/ie_rie_rediech/article/view/1013/1196

Lara, R. (2015). Mexican secondary school students’ perception of learning the history of Mexico in English. Profile, vol. 17, núm. 1, pp. 105-120. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n1.44739

Lasagabaster, D. & Doiz, A. (2016). CLIL students’ perceptions of their language learning process: Delving into self-perceived improvement and instructional preferences. Language Awareness, vol. 25, núm. 1-2, pp. 110-126, https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2015.1122019

Lodico, M., Spaulding, D. & Voegtle, K. (2006). Methods in educational research: from theory to practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Mäkipää, T. & King, S. (2021). Students’ and teachers’ perceptions of self-assessment and teacher feedback in foreign language teaching in general upper secondary education. A case study in Finland. Cogent Education, vol. 8, núm. 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1978622

Méndez-López, M. (2022). Emotions experienced by secondary school students in English classes in Mexico. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, vol. 24, núm. 2, pp. 219-233. https://doi.org/10.14483/2248708518.401

Normann, A. (2021). Secondary school students’ perceptions of language-learning experiences from participation in short Erasmus+ mobilities with non-native speakers of English. The Language Learning Journal, vol. 49, núm. 6, pp. 753-764. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1726993

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Organización (OECD) (2013). PISA 2012 Assessment and Analytical Framework: Mathematics, Reading, Science, Problem Solving and Financial Literacy. OECD Publishing.

Pardede, P. (2020). EFL secondary school students’ perception of ICT use in EFL classroom. Journal of English Teaching, vol. 6, núm. 3, pp. 247-259. https://doi.org/10.33541/jet.v6i3.2215

Programa Nacional de Inglés (PRONI) (2023). Cartas compromiso. https://educacionbasica.sep.gob.mx/proni/

Programa Nacional de Inglés (PRONI) (2022). Programa Nacional de Inglés. https://educacionbasica.sep.gob.mx/programa-nacional-de-ingles-proni/

Quadir, M. (2021). Teaching factors that affect students’ learning motivation: Bangladeshi EFL students’ perceptions. TEFLIN Journal, vol. 32, núm. 2, pp. 295-315. https://journal.teflin.org/index.php/journal/article/view/1560/356

Sabatier, P. (1986). Top-down and bottom-up models of implementation research: A critical analysis and suggested synthesis. Journal of Public Policy, vol. 6, núm. 1. pp. 21–48. http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0143814X00003846

Salim, H. & Hanif, M. (2020). English teaching reconstruction at Indonesian elementary schools: Students’ point of view. International Journal of Education and Practice, vol. 9, núm, 1, pp. 49–62. https://archive.conscientiabeam.com/index.php/61/article/view/690/1002

Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP) (2023). Diario Oficial, acuerdo número 08/08/23. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5698665&fecha=15/08/2023#gsc.tab=0

Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP) (2022). Plan de Estudios de la Educación Básica 2022. https://info-basica.seslp.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ULTIMA-VERSION-Plan-de-estudios-de-la-educacion-basica-2022-20-6-2022.pdf

Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP) (2018). Programa Sectorial de Educación 2013-2018. https://www.gob.mx/sep/documentos/programa-sectorial-de-educacion-2013-2018-17277

Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP) (2017a). Aprendizajes clave para la educación integral. https://subeducacionbasica.edomex.gob.mx/sites/subeducacionbasica.edomex.gob.mx/files/files/Aprendizajes%20clave(1).pdf

Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP) (2017b). Estrategia Nacional de Inglés. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/289658/Mexico_en_IngleDIGITAL.pdf

Tai, H. & Chen, Y. (2021). The effects of L2 proficiency on pragmatic comprehension and learner Strategies. Education Sciences, vol. 11, núm. 4, pp. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040174

Tsai, Y. (2021). Exploring the effects of corpus-based business English writing instruction on EFL learners’ writing proficiency and perception. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, núm. 33, pp. 475-498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-021-09272-4

Ünal, S., Çeliköz, N. & Sari, I. (2017). EFL proficiency in language learning and learner autonomy perceptions of Turkish learners. Journal of Education and Practice, vol. 8, núm. 11, pp. 117-122. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234640138.pdf

Vásquez-Guarnizo, J., Chía-Ríos, M. & Tobar-Gómez, M. (2020). EFL students’ perceptions on gender stereotypes through their narratives. Gist Education and Learning Research Journal, núm. 21, pp. 141-166. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.836

Velázquez, H. (2013). Fundamentos teóricos para un mejor aprendizaje del idioma inglés a partir de textos orales y escritos en estudiantes de tercer año de secundaria básica. Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores., vol. 1, núm. 2, pp. 1-35. https://dilemascontemporaneoseducacionpoliticayvalores.com/index.php/dilemas/article/view/97

Wright, S. (2004). Perceptions and stereotypes of ESL students. The Internet TESL Journal, vol. 10, núm. 2. http://iteslj.org/Articles/Wright-Stereotyping.html

Wu, B. (2022). Multilingual learners’ grammatical and pragmatic awareness in Chinese EFL context: from three layers of language awareness perspective. English Language Teaching, vol. 15, núm. 6, pp. 1-14. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v15n6p1

Yang, J. & Jang, C. (2020). The everyday politics of English-only policy in an EFL language school: practices, ideologies, and identities of Korean bilingual teachers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, vol. 25, núm. 3, pp. 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1740165

Zhiying, W. (2018). The effect of accent on listening comprehension: Chinese L2 learners’ perceptions and attitudes. THAITESOL Journal, vol. 31, núm. 2, pp. 47-71. https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/thaitesoljournal/article/view/193108

Zulkefly, F. & Razali, A. (2019). Malaysian rural secondary school students’ attitudes towards learning English as a second language. International Journal of Instruction, vol. 12, núm. 1, pp. 1141-1156. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2019.12173a

Appendices

Table 1

Survey section 1. General information

Table 2

Survey section 2. English language study background

Table 3

Survey section 3. Modalities of English language study

Table 4

Survey section 4. Background of Content-Based English study

Table 5

Descriptive Statistics of Low Proficiency and Intermediate Proficiency Students

Table 6

Dimension 1. Perceptions Regarding the Practice of English Skills

Table 7

Dimension 3. Self-Efficacy in Learning English