ISSN: 2007-7033 | Núm. 63 | e1675 | Open section: research articles

Pre-service English teachers’ learning traits

Rasgos de aprendizaje de los

profesores de inglés en formación

Óscar Manuel Narváez Trejo*

Cliserio Antonio Cruz Martínez**

Carolina Reyes Galindo***

The present study aimed to characterize a comprehensive learning profile of pre-service teachers at an English teacher education programme of a public university in Southeast Mexico. The learning attributes comprise their English entry level, learning strategies and styles, learning approaches, and learning preferences. The research design was non-experimental, descriptive transectional, with a single data collection procedure during the August 2023 term. Four learning scales and two placement tests were used to identify the predominant learning traits of the cohort studied. The results show a preference to use cognitive learning strategies more than any other type. In terms of learning styles, the findings show that most participants are primarily aural, but some students are bi- and even tri-oriented. In terms of their learning preferences, most students identified as analytical. Regarding learning approaches, most students typically employ a deep approach, which could be quite inadequate because they depend more on surface strategies.

Keywords:

learning traits, pre-service teachers, teacher education, EFL teaching

La investigación reportada tuvo como objetivo identificar los rasgos de aprendizaje de una cohorte de profesores de inglés en formación de una universidad pública en el sureste de México. Este estudio fue no-experimental, transeccional descriptivo. Los datos se recolectaron mediante cuatro escalas de aprendizaje y dos exámenes de colocación, lo que permitió identificar su nivel de inglés, las estrategias de aprendizaje que usan y los estilos de aprendizaje que poseen, así como sus enfoques y preferencias para aprender inglés. Los hallazgos de la investigación sugieren que existe una toral inclinación por el uso de estrategias de aprendizaje cognitivas. En relación con los estilos de aprendizaje, los resultados apuntan a una población con características de aprendizaje auditivas, aunque también emergieron participantes con dos o tres estilos de aprender distintos, como el analítico. En cuanto a sus enfoques de aprendizaje, los datos muestran que los estudiantes se decantan por un enfoque profundo, lo cual podría implicar una desarticulación entre sus enfoques y estrategias de aprendizaje del inglés en el contexto particular de la investigación.

Palabras clave:

rasgos de aprendizaje, maestros de inglés en formación, formación de profesores, enseñanza del inglés

Submitted: April 30, 2023 | Accepted for publication: October 15, 202 |

Published: November 1, 2024

Citation: Narváez Trejo, O. M., Cruz Martínez, C. A. & Reyes Galindo, C. (2024). Pre-service English teachers’ learning traits. Sinéctica, Revista Electrónica de Educación, (63), e1675. https://doi.org/10.31391/S2007-7033(2024)0063-014

* He is full-time professor at the School of Languages, University of Veracruz. He holds a Ph.D. from Kent University. He is interested in promoting teacher-based research to promote effective teacher education through technology enhanced teaching. E-mail: onarvaez@uv.mx/https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3259-2787

** He holds a PhD in Language Studies and Applied Linguistics from University of Veracruz (UV). He is a full-time professor at the School of Languages at UV. He is currently the Coordinator of the MA in Teaching English as a Foreign Language at UV. E-mail: clcruz@uv.mx/https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9444-1912

*** She holds an MA in Teaching English as a Foreign Language from the University of Veracruz. She has been a speaker in several national and international conferences and published articles and book chapters resulting from her research. E-mail: caroreyes@uv.mx/https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0281-5441

Introduction

The creation of undergraduate students’ profiles has become a common practice in universities around the world; these include general demographics of their newly admitted students which are then published on their websites. The information provided is valuable to have an idea of who the university students are. Research around the world has focused on undergraduate and graduate students’ engagement and persistence (Horn et al., 2006), their general technology experiences and expectations (Dahlstrom & Bichsel, 2014), their values (Thorpe & Loo, 2003), their ambitious characteristics (Marqués & Días, 2010), along with factors for predicting students’ academic performance (Alfan & Othman, 2006; Charry-Méndez & Cabrera-Díaz 2021).

Usually, the most common purpose for the creation of students’ profiles is to increase students’ academic success (Torres-Zapata et al., 2019). Nonetheless, there is no sufficient information available about how newly-admitted pre-service English teachers learn for teachers to have a profound knowledge of the student cohort.

It is very important to consider this issue for the success of each undergraduate program (Dórame et al., 2021). Only a few studies have been conducted concerning Mexico, specifically in the bachelor’s degree programs in language teaching and learning. Paredes and Chong (2015) led a study in which Mexican public universities researched their 2014 students’ trajectories. Their study reported results related to the student’s general and socio-economic background information and their high-school trajectories, along with their perceptions of their teachers, the curriculum, external and internal academic difficulties, expectations and tutoring at the university. Even though this has helped to create more detailed profiles of the newly admitted students, no information respecting their actual language level and learning traits has been obtained. Thus, the purpose of this study is to identify the newly admitted pre-service teachers’ English entry-level as well as to identify their learning styles, strategies, approaches and preferences to portray a more comprehensive profile, one that includes relevant individual learning differences.

This study aims to contribute to the understanding of the student population by providing information that adds to the data already provided by the university to create a more comprehensive learning portrait. Besides, there is little or no information available to understand the student population in terms of their learning traits available for teachers. Thus, this inquiry attempts to provide the institution with pertinent, up-to-date data on a cohort so that the institution and the faculty have more ground to make informed decisions about the quality of teaching they offer. Information of this type might help teachers to create tools and teaching strategies to support newly admitted students. Another objective is to help students become self-aware of their learning preferences so that they can use them to improve their education. In order to accomplish the goals, this investigation portrays this cohort in terms of their learning traits.

Learning profiles

Many aspects influence the learning process of English as a Foreign or Second Language (EFL/ESL). Among others, researchers have investigated the role of age, gender, culture and personality which account for some of the individual learning differences. Motivation, learning styles, learning strategies, learning preferences, and other notions are also associated with the concept of individual learning differences. Understanding learners’ different ways of learning can be used to create better classroom conditions to foster their language development. Thus, it is relevant for schools to find out as much information about the students they receive to create learning profiles (Torres-Zapata et al., 2019; Cortés & Birkner, 2023).

A learning profile aims to describe how a student learns best. A comprehensive learner profile includes information on student interests, learning preferences and styles, learning strategies and approaches (Cortés & Birkner, 2023). Since a comprehensive learning profile comprises many aspects, this study only focuses on identifying constructs believed to be highly influential in learning English, namely learning styles, learning strategies, learning preferences and learning approaches. Also included is the students’ entry level of English because the study takes place at a teacher education program which aims to reach the C1 level of the Common European Framework for Languages.

The following section reviews the most relevant literature related to the learning aspects considered to create this profile. This includes a definition of each term and the impact it may have on the learning trajectory of students.

Entry requirements in English teacher education programs

There are enough motives to identify newly admitted students’ learning preferences and abilities, including their English level, especially in learning English as a Foreign Language and English Language programs in Mexican higher education institutions. Several universities have assigned a minimum language level as an admission requirement. For example, at the University of Durango (s.f.), students are required a previous English knowledge equivalent to B1; the University of Hidalgo (s.f.) requests an A2 English level; the University of Baja California demands an intermediate or higher English level, and the University of Veracruz established a B2 English entry level for their online BA in TEFL.

Another example of an English program with entry language requirements is the Universidad de Guadalajara (2016) which requires students to obtain a minimum score in an oral and written English proficiency test applied by the same institution; however, there is no specification to which level it is equivalent. Also, the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (2012, 2016) request its English Teaching students an upper-intermediate proficiency level and good management of both written and oral communication in English. Nonetheless, most universities with this type of program, including the BA in English Language and Teaching of the University of Veracruz (2012, 2016), do not have a language-level entry requirement.

However, this does not create a problem itself considering that many students who arrive with zero or very little knowledge of English do manage to finish their degree satisfactorily. Nevertheless, analyzing in detail the newly admitted students’ abilities or needs does not seem to be a common practice among English Degree programs. This is very likely to hinder graduation rates. For example, at the University of Veracruz, not only is the English language section of the admission CENEVAL exam disregarded to calculate the candidates’ scores, including for the English BA; but it also provides very little information regarding other characteristics required by the programs as their ideal entry profile (Núñez et al., 2016). This lack of awareness of the admission requirements, together with the lack of detailed information regarding the student’s learning styles, learning strategies, learning approaches, and learning preferences, could be causing learning problems or no learning amongst students which in turn could explain the low proficiency level with which students are said to finish the degree. Were a more comprehensive profile of the students created, these problems could be mitigated.

A detailed analysis of the newly admitted students’ learning profile could have a positive impact on students’ overall performance and language achievement because knowing in depth who these students are might help institutions and teachers design more suitable instruction. The lack of awareness of the admission requirements, together with the inaccurate information regarding the student’s learning styles, strategies and so forth, may be causing low academic achievement or even dropping out.

Some universities have aimed to create a suitable profile for the students’ necessities. In the next section, this topic will be presented regarding other universities around the world which did some research for the creation of comprehensive profiles.

Comprehensive profiles

Some universities have created specific profiles of the newly admitted students to adapt to their needs, provide solutions to specific problems or increase the comprehension of different educational phenomena. For example, Marqués and Días (2010) performed a study to create a comprehensive profile of students majoring in engineering and business. Their findings suggested that specific entrepreneurial attributes were associated with certain students’ characteristics; for instance, female engineering students were somewhat more dedicated than other groups (Marqués & Días, 2010).

Similarly, the EDUCASE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR), surveyed 75,000 students to identify technology issues that could be used by the institutions so they could adapt their courses (Dahlstrom & Bichsel, 2014). The profile for this study was created with the students’ general demographics and information regarding students’ academic use of technology. The results showed that attitudes, information technology usage and disposition were not influenced by students’ age, gender, or ethnicity. The findings made clear the emphasis that students made on the use of mobile phones for different tasks related to academic or administrative issues in their institutions. Even though most students have a high inclination for the use of technology, a high number of them recognize themselves as not possessing enough skills to use technology in the development of their learning experience.

Dogan and Tatsuoka (2007) made a comparison between populations of Turkish and American students. For measuring the student’s performance on the TIMSS-R mathematics test; the Rule Space Model was used to analyze the results. In order to make an acceptable close match between the student’s item response pattern the examinee’s knowledge state (KS) classification was used. This test analyzed participants’ cognitive skills; this was applied to a population of 2,900 Turkish and 4,411 American students. The results showed that the weaknesses of Turkish students were algebra and probability/statistics; in addition, it was demonstrated a poor profile in skills such as applying rules in algebra, approximation/estimation, solving open-ended problems, recognizing patterns and relationships and quantitative reading in comparison with the American student. Thanks to this research, the researchers and educators learned about the weaknesses of their students.

Two other studies created a profile to understand academic failure, and thus have a better idea of what to do to improve students’ performance. The National Center of Education Statistics (NCES) created a demographic profile which allowed them to explain the low rate of completion in the acquisition of associate or bachelor degrees (Horn et al., 2006); while the University of Malaya performed a study in its faculty of Business and Accountancy to investigate the relationship between the characteristic of the students (like their social background or gender) and their performance level throughout their degree program (Alfan & Othman, 2005). The data of 314 graduates was analyzed in this study, respecting their demographics, academic results before enrolling in university, number of periods spent in the degree program, and finally their final summative grade point average. The results determined that is necessary the increment students’ knowledge in specific areas as math and doing this may reduce the number of dropouts in business and accounting programs.

In the context of the study, we could only identify one previous study related to this one. Estrada et al. (2016) carried out a similar study in 2014 to create a detailed demographic profile of the 2014 cohort. The profile created is shown in the following table.

Table 1. Demographic profile of the research population

|

Demographic Profile |

||||

|

Sex |

Male (39.8%) |

Female (60.2%) |

||

|

Marital Status |

Single (94.4%) |

|||

|

Age |

18 (48.1%) |

|||

|

Origin Locality |

State |

State of Veracruz (84.3%) |

||

|

Outside of Xalapa (66.7%) |

||||

|

Work |

No (87%) |

|||

|

Studies |

Father |

No higher education (63.9 %) |

||

|

Mother |

No higher education (72.2 %) |

|||

|

Social Status |

Middle class (65.7%) |

|||

|

Previous Studies |

Public system (87%) |

|||

|

GPA in High School |

8.0 - 8.9 (54.6%) |

|||

In a follow-up study, Estrada et al. (2016) studied the 2014 cohort. For this study, a questionnaire was administered to 108 participants. Apart from providing demographic information about this student cohort; the instrument gathered information about students’ perception of teachers’ performance and the theoretical and practical knowledge of the courses. Also included were students’ perception of the BA program, students’ perception of academic difficulties due to external factors, students’ perception of academic difficulties due to personal factors, students’ vocational beliefs and expectations, and students’ perception of the tutorial experience. In conclusion, the main two factors that the researchers detected as possible problems for this cohort were poor study habits and a lack of stress-management skills.

In brief, the studies presented here show that no other universities nor researchers have aimed at identifying students’ learning traits. However important, no previous study on that behalf had been done. This study aims to depict pre-service English teachers’ learning characteristics that include academic aspects which certainly influence academic performance. In what follows, a discussion of the components of the learning profile are presented and discussed.

Learning strategies

The term learning strategies has been defined in several ways by different authors. Learning strategies are the approaches and techniques that students take to ease their learning and remember both linguistic and content information (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990). Wenden and Rubín (1987) states that learning strategies are the language learning behaviours which learners use for their learning and regulation of the second language acquisition, as well as the aspects of the strategies they use. Nunan (1992) states that learning strategies are mechanisms that learners practice to aid the acquisition, storage, retrieval, and use of information. Another definition provided by Oxford (1990) states that language learning strategies are the actions which students take to improve their language learning because they are tools for active, self-directed involvement, which is the basis for the development of communicative competence; the learning strategies are base in helping students to become autonomous learners. At the same time, the learning strategies are processes or behaviors executed by the learners to improve their learning, but these processes influence the learners’ characteristics like learning styles, motivation and aptitudes.

From a teaching perspective, research has shown that strategies are teachable provided instruction is direct and explicit; and that strategies instruction contributes to improved language performance and proficiency (Alghamadi, 2016). Research has also shown that the instructional sequence to introduce strategies (present, model, explain and provide practice) is an approach that all teachers can attend to successfully; and the instructional sequence can be adapted to match the needs, instructional resources, and time available according to the learning-teaching context (Jourdan et al., 2022). Therefore, integrating language learning strategy instruction into ESL/EFL classrooms is a challenge that all language teachers should take because not only does it help learners become more efficient in their efforts to learn a second or foreign language, but it also provides a meaningful way to focus one’s teaching efforts.

Regarding learning strategies, Alghamadi (2016) supports the idea that strategy training is important for EFL learners, especially to increase their self-directedness, autonomy, and motivation. Self-regulated learning strategies have also proved to be fundamental not only in face-to-face environments but also in those online (Broadbent & Poon, 2015). Additionally, in a study carried out with university students in Turkey, Altmisdort (2016) concludes that strategies can be grouped into learning and acquisition strategies, that students should be able to distinguish to use them more effectively, and that attitudes towards language learning and acquisition are key factors in successful learning. To assess language learning strategy use, the most widely known and used instrument is the ESL/EFL version of the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL). This is based on the correlation between strategies use and language performance, as well as sensory preferences, and is cross-culturally reliable (Oxford & Burry-Stock, 1995). This is one of the instruments used in the present study.

Learning styles

As researching learning styles, it is reasonable to associate them with teaching styles. Nevertheless, matching learning and teaching styles might not always be the best path to follow (Tulbure, 2012; Zhou, 2011). Although it is partially supported by literature that a given learning style will respond better to a matching teaching style, sometimes students have better results with a teaching strategy which differs from the most associated characteristics of their learning styles (Tulbure, 2012). Moreover, mismatching learning and teaching styles may “help [English language] students to learn in new ways and to bring into play ways of thinking and aspects of the self not previously developed” (Zhou, 2011, p. 76). Learning styles have also been related to learning strategies, and it has been found that the former changes according to the latter (Kafadar & Tay, 2014; Rodríguez-Guardado & Juárez-Díaz, 2023) and with learning approaches (León-Sánchez & Barrera-García, 2022) as both constructs relate to how students learn.

Given the many different definitions, theorists, and classifications for learning styles, using them to promote more effective learning constitutes a highly challenging enterprise for educators. That is why doing research in this field is important to “contribute to the development of a unifying conceptual and empirical framework of learning style” (Cassidy, 2004, p. 441). The present study, however, does not attempt to contribute in this specific area, as its purpose addresses the creation of a student’s profile rather than deepening the theorizing of learning styles.

The term learning styles is widely used to describe how learners gather, sift through, interpret, organize, come to conclusions about, and “store” information for further use. As spelt out in VARK (one of the most popular learning style inventories), these styles are often categorized by sensory approaches: visual, aural, verbal [reading/writing], and kinesthetic. These learning styles are guides that learners follow to make their learning process more effective. In addition, according to Cohen et al. (1996) the learning styles are conscious brain processes and behaviors that the learners employ to ease the language learning task and make the language learning process their own. Basically, learning styles bases on the idea that each student has a specific learning style or “preference”, and they learn best when information is presented to them in this style. For example, visual learners would learn any subject matter best if given graphically or through other kinds of visual images, kinesthetic learners would learn more effectively if they could involve bodily movements in the learning process, and so on. The message thus given to instructors is that “optimal instruction requires diagnosing individuals’ learning style[s] and tailoring instruction accordingly” (Pashler et al., 2009, p. 105). Thus, the importance of identifying the students’ learning styles (Sánchez-Cotrina, 2023).

Learning approaches

According to Dilek and Nuray (2015), learning approaches can be defined in terms of how a learner’s intentions, behavior and study habits change according to their perceptions of a learning task. The construct of learning approaches has been utilized to enhance teaching modules or as a basis for understanding student cohorts (Freiberg & Vigh, 2021), yet very few studies have been conducted in higher education in Mexico.

Noor (2006, as cited in Narváez et al., 2019) claims that in essence, the learner who adopts a deep approach are intrinsically motivated, focuses on understanding the content of the learning material, relates parts to each other as well as new ideas to previous knowledge. On the other hand, the surface learner is extrinsically motivated, focusing on memorizing for assessment purposes and seeking to meet the demands of the task with minimum effort. Research has shown that shifting from traditional instructor-dominated pedagogy to a learner-centered approach leads to deeper levels of understanding and meaning for students (Sim 2006, as cited in Narváez et al., 2019).

Biggs’ learning processes model, which combines motivation (why the student wants to study the task) and their related strategies (how the student approaches the task) outlines three common approaches to learning: deep, surface and achieving (Biggs, 1993). When students are taking a deep strategy, they aim to develop understanding and make sense of what they are learning and create meaning and make ideas their own. This means they focus on the meaning of what they are learning, aim to develop their own understanding, relate ideas together and make connections with previous experiences, ask themselves questions about what they are learning, discuss their ideas with others and compare different perspectives (Medina et al., 2023). When students use a surface strategy, they aim to reproduce information and learn the facts and ideas—with little recourse to seeing relations or connections between ideas. When students are using an achieving strategy, they use a ‘minimax’ notion—minimum amount of effort for maximum return in terms of passing tests, complying with instructions, and operating strategically to meet a desired grade. It is the achieving strategy that seems most related to school outcomes (Valle et al., 2000).

Learning preferences

Identifying students’ learning preferences is a necessary step towards maximizing students’ level of achievement; it basically answers the question: how do students like to learn? Knowing this is an initial step in the development of a learner-centered classroom (Nunan, 2013); which in turn involves training learners to identify their own preferred learning styles and strategies.

For effective language learning and teaching, both learner skills and learner assumptions should be given due attention. In promoting this idea, students should be provided with the opportunity to clarify and assess their preferences. Learners and learners’ preferences are of crucial importance in the development of learner autonomy. Bada and Okan (2000) asked 230 students at the ELT Department, Faculty of Education, Cukurova University, to state their views as to how they prefer learning English. As a further step, 23 teachers working at the same department with the same students were also asked to express their views regarding the extent of their awareness of their students’ learning preferences. The data obtained reveal significant results suggesting a need for a closer co-operation between students and teachers as to how learning activities should be arranged and implemented in the classroom. The instrument used in this study has been used successfully with learners in many different pedagogical situations (Nunan, 2013).

Differentiated learning

The principles of differentiated learning are rooted in several years of educational theory and research. This method adopted the concept of “readiness”, which refers to the level of difficulty when teaching or developing students’ specific skills because not all students own the same learning styles and skills (Hall, 2002). This model requires flexibility from the teachers in their approach and adjustment of the curriculum and the way to present the information, rather than students adjusting themselves to the curriculum. Accordingly, differentiated Instruction is based on the belief that the approaches should vary and be adapted to students’ individual necessities (Hall, 2002).

According to Tomlinson et al. (2003), some research suggests that most teachers adjust in an insufficient form how they give instruction in an effective way in order to influence several populations; they add that it is plausible because many teachers are unknowing of the students’ learning-profile preferences that they do not evolve the necessary skills for success. Even though differentiation is identified for being an assembling of many theories and practices, it lacks empirical validation, and for that reason this area needs future research (Hall, 2002).

With this being said, differentiated learning is important to be considered because when creating the curriculum for the institution it is necessary to consider the abilities and disabilities that the students have and adapt the curriculum to their necessities (Tomlinson, 2017).

Entry English level

There seems to be a scarcity of information regarding students’ entry level. Nonetheless (Núñez et al., 2016) report a previous study in which two separate tests were applied to measure the English proficiency level of students in the cohorts 2014 and 2015. One test was the placement test provided by the LIFE National Geographic Learning, the course book selected by the BA for language courses. As well, a KET sample test was applied to students in both cohorts. In 2014, more than 50% of the students were placed in an elementary level by both placement tests while less than 25% were graded as pre-intermediate learners. In 2015, about 50% of the students were situated in the elementary level, and 35% were graded as lower-intermediate. The results obtained from both tests were used to adapt the contents of the language courses appropriately to the English Language program (currently going from A2 to C1, previously going from A1 to C1).

It is important to consider that the purpose of this study is the depiction of general learning traits of newly-admitted pre-service English teachers in order to provide educational actors the necessary tools to adapt the curriculum to students’ specific learning characteristics. This creates an opportunity for further research to find out whether the students have the needed profile to be admitted to the BA or not, and what educational strategies might be followed to respond to their learning profile so as to help them achieve a better command of the language and complete their studies successfully.

Methodology

Following a quantitative stand, this is an exploratory, descriptive study (Seliger & Shohamy, 1989) which employed six survey-like instruments as its main form of data collection. The data collected is reduced to the specific aim of each of the instruments; that is, each one has been specifically designed to identify a learning characteristic of students that comes into play when learning English as a Foreign Language. As Creswell (2003) states, this approach mainly consists of doing experiments and surveys, then the data is collected using predetermined instruments which provide statistical and precise data. This approach fits this study because it aims at measuring different aspects of students’ learning and background.

Being quantitative, this study was a case study, in which a researcher can examine a situation within its context, limited by time and activity, and collect detailed information (Merriam, 1998; Yin, 2003). The case that was investigated concerned pre-service English teachers learning characteristics, which, together might provide a prevailing learning profile.

Context

The study took place at a BA Degree in English Language and Teaching (DELT hereafter) at a large state university in Southeast Mexico. It admits 220 students each year (approximately 40% of the demand).

According to the 2023 curriculum, the DELT aims to train students to develop a command of English equivalent to the C1 level in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) and to provide students with the competencies needed to perform adequately in teaching English.

Given the characteristics of a DELT education, there is a strong component of English courses made up of seven different levels: Elementary, Pre-Intermediate, Intermediate, Intermediate Plus, Upper Intermediate, Advanced and Advanced Plus. The English courses are based on the Common European Framework of Reference levels (A2 to C2).

The teaching staff consists of 66 teachers of which 32 are tenured, 22 are permanent teachers, and 12 are under term contracts. Twelve per cent of the teachers hold a PhD degree, 75% hold a master’s degree, 6% have a Diploma in TEFL, and 7% have a BA degree. The teaching staff is well qualified with 93% having postgraduate studies.

Participants

The number of students which were admitted into the English BA was 220 students which are divided into 8 groups of approximately 26-28 students. For this study and for the sake of convenience, only 4 groups were invited to participate (n=104). These groups can be taken as representative samples considering that the admitted students are randomly placed into eight groups. They were chosen because the study aims to provide a comprehensive academic profile of students as they arrive at the university. Therefore, it was a very good opportunity to provide new and fresh information about the students’ learning traits.

The instruments

To identify students’ learning traits, four inventories that have been designed specifically for each aspect investigated and used widely were administered to the target population. Taken together, these might provide deeper understanding of the type of learners admitted. Each instrument was typed into a Google forms template. All their answers were stored in an online database created in Google Spreadsheets, which allowed an automatic access to the data. Subsequently, the tables and graphics were created using the available tools in Google Spreadsheets. The following table describes the characteristics measured in the instruments.

Table 2. Instrument and the traits they identify

|

Instrument |

AIM |

|

The Learning Approaches Questionnaire |

The LPQ is a 36-item self-report questionnaire that yields scores on three basic motives for learning and three learning strategies, and on the approaches to learning that are formed by these |

|

VARK (learning styles) |

The aim of this instrument is to understand students’ preferred sensory modality (or modalities) for learning |

|

Strategies Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) Version 7.0 (ESL/EFL) (© R. Oxford. 1989) |

The SILL is a tool that students and teachers can use to assess the specific language learning strategies that are employed by the student in learning a foreign language |

|

The Learning Preferences questionnaire |

This questionnaire identifies students’ preferences relating English learning |

In order to discern the newly admitted students’ English entry level two English diagnostic/placement tests were applied. The Pearson test was chosen because the textbooks used in the English courses belong to this publishing company. It comprises 80 items divided in the following way: Listening (20 items, Grammar 30, Vocabulary 20 and Reading 10); and depending on the number of correct marks it states the testees’ English level.

The other test was The Outcomes Placement Test Package (Cengage Learning) which was developed to help course providers place students in the most appropriate level. This consists of 50 items testing grammar and vocabulary.

Both tests have been developed to help institutions place students into the most appropriate level of a course or program. Students who took these can be placed into a course/program ranging from CEFR A1 to B2+. They include language commonly used in British English and are most suitable for placement into a British English course, which is the case.

Findings

This section presents and discusses the findings of the study. It first starts with the results of the English exam. Second, the findings related to students’ learning approaches are shown. Thirdly, we present the results obtained from the VARK questionnaire, related to students’ learning styles. Then, we analyze the results from the SILL which provides information regarding students’ learning strategies. Finally, the results of the learning preferences are presented.

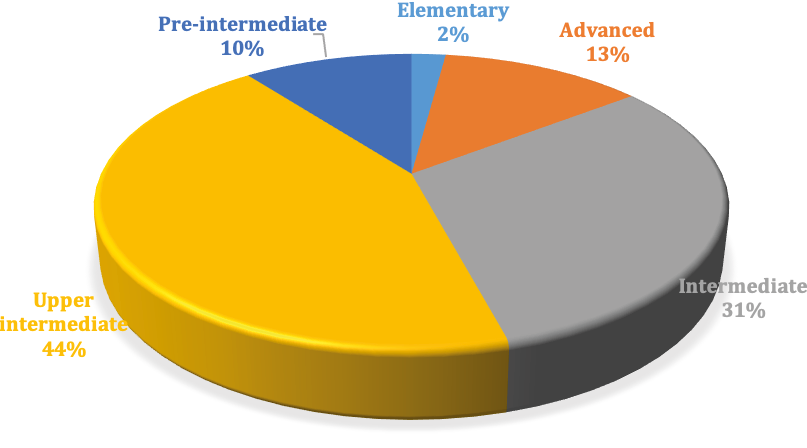

English level

As mentioned above, two different diagnostic tests were administered to identify newly admitted students’ entry English level. Results from the Outcomes test indicate that 43.8 % of the students were identified as having an upper intermediate level. 31.3 % obtained an equivalent to an intermediate level, 12.50% got a score equivalent to an advanced level while 10.4% of the students obtained a score equivalent to a pre-intermediate English level. Only one student (2.1%) obtained a result corresponding to the elementary level. These results are shown in the graph below.

Graph 1. English entry level

Results from the Pearson Placement test were similar. Graph 2 below clearly shows that almost half the students surveyed belong to the A2+ level (pre-intermediate students) while the same amount was placed in the intermediate level. Only 6.7% were placed in the B1+ level, which means that only a few students have an upper intermediate level.

Graph 2. Pearson placement test

Results from both placement tests seem to indicate that students’ entry level is not as low as expected. Only few students taking the Elementary level course of the institution (level A2) are rightfully taking a level corresponding to their actual English level while the vast majority seem to have a higher level than that offered by the school.

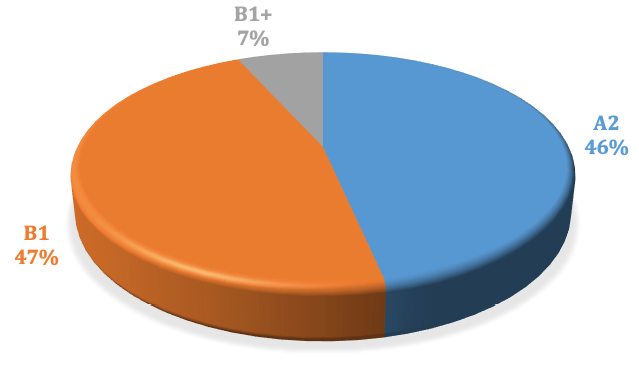

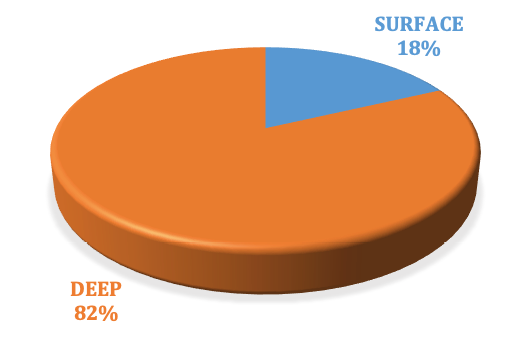

Learning approaches

Regarding the learning approaches that the group of PSET favor, it was found out that 82% of the participants tend to use a Deep approach to learning whereas only 18% favour a surface approach.

Graph 3. Approach

These findings mean that students tend to favor Deep motive (items 1,5,9,13, and 17) that is related with intrinsic motivation, comprehension, the satisfaction of curiosity and the transformation of information into knowledge; and Deep strategy (items 2, 6, 10, 14, 18), associated with reproduction with precision without reflections, learning by memorization, matching ideas, argumentation and the use of information to get to conclusions. This means that through the connection of new ideas with previous knowledge and experiences what is learned is comprehended.

Deep motive and deep strategy are developed in the deep approach, in which motives are related with the competence of the students to obtain better academic performance. The strategies are associated with time management, self-discipline and planning. In other words, students organize their study habits which are reflected in their academic production. Certainly, those habits may include the characteristics previously mentioned.

Regarding those students who lean towards a surface approach (18%), they tend to reproduce information to avoid failure leading them to obtain low scores. They depend on memorization and association of concepts without reflection.

Surface motive and surface strategies are developed in the surface approach, when students do not demonstrate an interest in learning new concepts due to the strategies generated by the feeling of imposition on behalf of the teachers, which can cause monotony.

Table 3. Intensity of approaches

|

Intensity |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Low surface |

10 |

18 |

|

Low deep |

38 |

68 |

|

Medium deep |

8 |

14 |

Although the deep approach prevails among the participants, the intensity of the approach differs. Most students using a deep approach tend to use a low deep approach, which can be interpreted as a ‘light’ form learning approach. This can be seen in Table 3.

Finally, another important finding was that female students tend to develop their deep approach more than men. As it can be seen in Table 4, 64% of the population is represented by women in the deep approach categories.

Table 4. Genre

|

Genre |

Deep |

Surface |

|

Male |

36% |

56% |

|

Female |

64% |

44% |

The results indicate a positive trend towards a deep approach to learning. However, the nuance lies in the intensity of this approach. The majority of PSET lean towards a deep approach, which is encouraging as it suggests a focus on understanding and critical thinking. This can be be attributed to students’ perceptions of their ability to perform the required learning tasks and their perceptions of teachers’ ability to impact student learning and behaviour. Nonetheless, the intensity is rather low. This implies that while PSET are generally motivated to learn, their strategies might not be as effective as desired. This suggest a promising foundation for deeper learning but there is room for improvement.

VARK styles

This section consists of data presentation and analysis of the VARK questionnaire. The participant students have various learning style preferences. Their learning style preferences are divided into two parts, those who showed Single preference and Bi-modal preference.

The single preference is grouped into four preferences, those are Visual (V= 5.5%), Aural (A=31.5%), Read/Write (R=18.5%), and Kinesthetic (K=26%) (see Table 5). The next group is Bi-modal divided into five parts, those are VR, VA, AK, AR, and RK, which corresponds to 16.6 of the surveyed population. Only one student reported being Tri-modal, showing preference towards ARK.

Table 5. The students’ VARK style

|

Type of preference |

Occurrences |

|

Visual |

5.55% |

|

Aural |

31.48% |

|

Read/Write |

18.51% |

|

Kinesthetic |

25.92% |

|

Total |

81.48% |

Table 6. Single preference occurrence

|

Type of preference |

Percentage |

|

Single preference |

81.48 |

|

Bi-modal preference |

16.66 |

|

Tri-modal preference |

1.85% |

|

Total |

100 |

Table 6 displays how the single preference occurrence is distributed. The most preferred learning style is Aural with a percentage of 31.84%. Kinesthetic preference is second with a percentage of 25.91%. The third sequence is Read/Write with 18.51%. Based on this data, we can observe that a significant portion of the PSET learns best through listening, discussions and verbal explanations. Kinesthetic learning is the second most preferred style which indicates that practical, hands-on experiences are a strong learning preference for a considerable number of participants.

These findings have significant implications for instructional design and delivery. Teachers must incorporate clear explanations, create discussion activities and use audio-visual materials to cater to the largest learning style preference. To engage kinesthetic learners, teachers must include practical activities, role-plays or simulations.

Table 7. Bi-modal preference occurrence

|

Type of preference |

Occurrences |

|

VR |

1.85% |

|

VA |

1.85% |

|

AK |

3.70% |

|

AR |

5.55% |

|

RK |

3.70% |

|

Total |

16.66% |

Table 7 presents Bi-modal preference occurrence which is grouped into five parts. Based on the table above, type AR has a percentage of 5.55%. Next, types RK and AK have the same percentage of 3.70%. The last types are VR and VA with the same percentage of 1.85%.

These findings are similar to those reported by Fernández and Narváez (2021). It can be concluded that learning styles encompass not only the comprehension and absorption of information but also the application of the knowledge being imparted. Teachers must ascertain students’ learning styles in order to choose suitable instructional strategies, methodology or resources that can optimize students learning. Furthermore, having this knowledge, might enable teachers to develop lesson plans that are tailored to their students’ specific requirements. In addition, teachers can assist students in cultivating other learning styles and enhancing the style that is most prevalent by providing them with enduring activities for developing their language skills and knowledge. Nonetheless, it is crucial to consider additional variables that can alter students’ learning style preferences, such as motivation, context and the length of language exposure.

Learning strategies

This section presents the results of the SILL instrument, concerning the learning strategies that participants use according to response rates. Results of the descriptive statistics showed that the mean strategy use by the participants on the whole strategy was 3.38, indicating that they were medium strategy users. Table 8 presents the descriptive strategy categories used.

Table 8. Mean and SD of the whole strategy use and the 6 strategy categories

|

Strategy category |

Mean |

SD |

|

Memory strategy |

3.34 |

0.25 |

|

Cognitive strategy |

3.48 |

0.11 |

|

Compensation strategy |

2.91 |

0.12 |

|

Metacognitive strategy |

3.86 |

0.19 |

|

Affective strategy |

3.16 |

0.20 |

|

Social strategy |

3.52 |

0.12 |

|

Overall strategy use |

3.38 |

0.05 |

The Metacognitive strategies showed a high mean of 3.86 and SD of 0.19, all over other categories. The next most frequently used strategy was Social strategies with a mean of 3.52 and SD 0.12, followed by Cognitive strategies with a mean of 3.48, and SD of 0.11. After that Memory strategies were found with a mean of 3.34 and SD of 0.25. The next set was Affective strategies with a mean of 3.16 and SD 0.20. Finally, Compensation strategies were found with a mean of 2.91 and SD of 0.11.

Further analysis lets us identify that among the most frequently used strategies, five were metacognitive. Strategies such as, “I think about my progress in learning English,” “I try to find out how to be a better and more effective learner of English,” or “I notice my English mistakes and use that information to help me do better” all show that the participants were conscious of the process of their learning and tried to have control over their learning. All these strategies were used at a high level.

The reason why metacognitive strategies were the most frequently used might be the fact that they are learning English in an EFL context; that is, these learners do not have much exposure to the target language to pick it up unconsciously. In fact, due to the lack of enough exposure to the target language, they hardly have any chance to unconsciously pick up the target language. Through conscious attention to the language learning process, they can compensate for this deficiency, and that is why metacognitive strategies appear to be used at such a high level. Furthermore, in most English classes, teachers usually place a lot of emphasis on explaining the language and making the learners’ conscious of the process of learning even in cases where the communicative approach is adopted.

These results revealed a pronounced preference for metacognitive and social learning strategies among PSET. This suggests a student population adept at self-regulated learning and collaborative approaches. These outcomes may be attributed to students’ need to develop independent learning skills in a context often characterized by limited instructional resources. Additionally, the strong emphasis on social learning strategies aligns with the collectivist cultural orientation prevalent the Mexican context.

These results carry significant pedagogical implications. Considering PSET demonstrated proficiency in metacognitive and social strategies, instructional efforts should focus on incorporating self-directed learning components and fostering collaborative learning environments to build upon these strengths. Moreover, to address the relatively lower utilization of affective and compensation strategies, interventions aimed at emotional regulation and problem-solving skills might be beneficial.

These findings suggest that students tend to rely more on strategies that help them plan, monitor and regulate their learning (metacognitive strategies) nand interact with classmates to learn (social strategies) compared to strategies focused on managing emotions or compensating for knowledge gaps. These results imply that these PSET may benefit from instructional interventions that focus on strengthening metacognitive and social learning strategies.

Learning preferences

To discover whether students prefer communicative, concrete, authority-oriented, or analytical learning preference, descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were computed. The one indicating the highest mean value was considered the preferred learning preference. Table 9 shows the mean and standard deviations of the four distinct categories. Responses to the statements of type four (analytical) had the highest mean value of 2.84 and a standard deviation of 0.95, while the responses to Concrete type of learning preference had the lowest mean score of 2.28 and a standard deviation of 0.18.

These results suggest that the majority of PSET in this sample have a higher preference for analytical learning with a mean score of 2.84. This suggests that PSET tend to learn better through analysing information and identifying patterns. These students have a lower preference for Concrete learning, which indicates that students, on average, show a lower preference for hands-on experiences and practical applications.

Table 9. Mean and SD of learning preferences

|

Learning style |

Mean |

SD |

|

Analytical |

2.84 |

0.95 |

|

Authority-oriented |

2.53 |

0.13 |

|

Communicative |

2.39 |

0.08 |

|

Concrete |

2.28 |

0.18 |

|

Overall style use |

2.51 |

0.41 |

Based on the results, the item “I like to study English by myself” scored as highest mean value of 3.32 and a standard deviation of 0.75 whereas the lowest mean value of 2.49 with a standard deviation of 0.79 was noted for the item “At home, I like to learn by reading English web pages”. This means that analytical types of learners are independent who tend to find solutions for their problems while learning. Analytical learners’ cognitive strengths guide them not only to analyze carefully and reveal great interest in structures, but also to put a large amount of value on showing their independence by doing these things themselves, autonomously (Willing, 1988). In general, it can be inferred from these findings that media such as streaming platforms, videos and movies are powerful devices for learning foreign languages in contexts in which English is learnt as a foreign language in which it is learned and spoken only in classes. According to Celec-Murcia (2001), such media motivate learners by bringing real-life situations into the classroom and presenting language in its more complete communicative context.

Table 10. Types of learning preference

|

Learning preference |

Ocurrences |

|

Single preference |

68.42% |

|

Bi-modal preference |

23.68% |

|

Tri-modal preference |

7.89% |

|

Total |

100% |

Something important to highlight is the fact that over 30% of the participants show a mixed modal preference (see Table 10). Even though the vast majority have a single preference, some students demonstrated a bi-modal or even a tri-modal learning preference. This implies that learners may prefer different instruction modes to achieve their learning goals.

These results suggest that students generally prefer analytical learning approaches. However, there is some variability in these preferences, with some students likely scoring higher on analytical learning than others. In contrast, the scores for authority-oriented and communicative learning are more consistent, suggesting that most students have similar preference levels for these styles.

These results have relevant instructional implications as they can inform instructional approaches to cater to diverse learning styles in the classroom. Since most PSET are analytical learners, instructional practices ought to involve information analysis, problem solving and critical thinking through research projects and simulations that require students to analyse information and draw conclusions. To provide opportunities for authority-oriented learners, they should learn from experts in the field. This could involve guest lectures, presentations by more experienced professionals or incorporating readings from authoritative sources.

Conclusion

The reported study aimed to portray PSET’ learning traits in terms of learning strategies, learning styles, approaches, preferences and their entry English level.

By using specifically designed instruments it was possible to identify participants’ learning characteristics. The relevance of knowing students’ learning attributes relies on the fact that no other study had previously aimed at identifying these learning traits in a single research with the same population. In that sense, the data hereby provided is a breakthrough. This can serve not only the institution to make informed decisions regarding its teaching philosophy and curriculum but also students to act and improve as they advance in their studies.

The study yielded data that let the researchers answer the research questions guiding it. Regarding students’ learning strategies, it was found that most students tend to use cognitive strategies more than any other type. Concerning VARK learning styles, the results indicate that participants are mostly single-style oriented, mostly Aural, but some students are bi and even tri-style oriented. As for the learning preferences, most students reported being Analytical students. Relating to learning approaches, most students tend to use a Deep approach to learning but this is very weak since they rely more on Surface strategies.

The findings of this study align with a substantial body of research on learning approaches, styles and strategies. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated the predominance of deep learning approaches among university students (Marton & Saljo, 1976; Entwiste, 1981; Narváez et al., 2019). However, the findings of a predominantly low-intensity deep approach extend these observations, suggesting a need for further investigation into the factors influencing the depth of students’ engagement.

The relationship between learning styles and approaches is a complex one. While VARK has been widely used to assess learning preferences, its predictive validity for academic performance has been debated (Coffield et al., 2004). Nevertheless, the findings in this study support the notion that considering multiple dimensions of learning, including both approaches and styles, can provide valuable insights into students´ learning experiences.

The concept of a light deep approach resonates with research on surface and strategic learning (Biggs, 1987). While PSET may exhibit elements of deep learning, such as motivation and curiosity, they might lack the strategic study skills necessary to capitaliza on ther potential. This findijg highlights the importance of developing effective learning strategies among the PSET.

In short, it would be beneficial for the institution to take this information into account and provide first-semester PSET as many opportunities to use the language as possible since the kind of instruction and learning profile seem to go hand in hand. By implementing conversation clubs and other types of academic support, students could complement their learning by expanding their learning opportunities.

Regarding the PSETs’ entry proficiency English level, the results indicated that they already have a certain degree of English knowledge falling within the pre-intermediate and intermediate categories. Consequently, despite the absence of a prerequisite English level in the DELT program, newly enrolled PSET are admitted to the institution with a higher level of preparation than expected.

Students are required to meet the criteria outlined on the institutions’ webpage in order to be considered qualified for admission to the BA. The learning traits hereby portrayed indicate that their learning characteristics are deemed appropriate. However, it is imperative for teacher educators at this institution to inspire and encourage students to maintain their motivation for the BA. It is expected that teacher educators take advantage of the information here addressed to enhance their teaching by developing specific strategies to cater for students learning needs.

This study contributes to the existing body of research on learning approaches, styles, preferences and strategies by providing empirical evidence of the prevalence of a low-intensity deep approach among the studied population The findings underscore the complexity of students learning and the need for multifaceted interventions to enhance academic performance.

By combining insights from learning approach theories, learning style models and previous research, educators can develop more effective instructional strategies. Further studies could explore the longitudinal impact of learning approaches on student outcomes, investigate the effectiveness of specific interventions to deepen learning, and examine the role of technology in shaping learning experiences.

References

Alfan, E. & Othman, N. (2005). Undergraduate students’ performance: The case of university of Malaya. Quality Assurance in Education, 13(4), 329-343. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880510626593

Alghamadi, A. (2016). Self-directed learning in preparatory-year university students: comparing successful and less-successful English language learners. English Language Teaching, 9 (7), 59-69.

Altmisdort, G. (2016). Assessment of language learners’ strategies: Do they prefer learning or acquisition strategies? Academic Journals, 11 (13), 1202-2016. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2016.2755

Bada, E & Okan, Z. (2000) Students’ Language Learning Preferences. TESL EJ, 4 (3), 1-15. https://www.tesl-ej.org/ej15/a1.html

Biggs, J. B. (1993). What do inventories of students’ learning processes really measure? A theoretical review and clarification. British J. Educ. Psychol., 63, 3-19.

Biggs, J. B. (1987). Student approaches to learning and studying. Edinburgh University Press.

Broadbent, J. & Poon, W. (2015). Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher educationlearning environments: A systematic review. The Internet and Higher Education, 27, 1-13.

Cassidy, S. (2004). Learning styles: An overview of theories, models, and measures. Educational Psychology, 24, 420-444. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0144341042000228834

Celce-Murcia, M. (2001). Teaching english as a second or foreign language. 3rd Edition. Heinle & Heinle Publisher.

Charry-Méndez, S. & Cabrera-Díaz, E. (2021). Perfil del estilo de vida en estudiantes de una Universidad Pública. Revista Ciencia y Cuidado, 18(2), 82-95.

Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E. & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Should we be using learning styles. Learning and Skills Research Centre.

Cohen, A. D., Weaver, S. J. & Li, T.-Y. (1996, June). The impact of strategies-based instruction on speaking a foreign language. http://carla.umn.edu/resources/working-papers/documents/ImpactOfStrategiesBasedInstruction.pdf

Cortés, T. & Birkner, V. (2023). Trazando el perfil de ingreso del estudiante universitario: un estudio de caso en la Universidad Silva Henríquez. Revista Invecom, 3(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8146813

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches I (2nd ed.). University of Nebraska.

Dahlstrom, E. & Bichsel, J. (2014). ECAR study of undergraduate students and information technology, 2014 Educause Center for Analysis and Research. https://library.educause.edu/~/media/files/library/2014/10/ers1406.pdf

Dilek, G. & Nuray, N. (2015). Learning approaches of successful students and factors affecting their learning Approaches. Education and Science, 40 (179), 193-2016. https://doi.org/0.15390/EB.2015.4214

Dogan, E. & Tatsuoka, K. (2007). An international comparison using a diagnostic testing model: Turkish students’ profile of mathematical skills on TIMSS-R. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 68(3), 263-272. https//doi.org/10.1007/s10649-007-9099-8

Dórame, D. L., Ávila, M. Á. T. & Zayas, M. Y. T. (2021). Perfil de ingreso: características socioeducativas y familiares en estudiantes del primer año de universidad privada en Sonora, México. Praxis Investigativa ReDIE: revista electrónica de la Red Durango de Investigadores Educativos, 13(25), 40-54.

Entwiste, N. (1981). Styles of learning and teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Estrada, G., Narváez, O. & Núñez, P. (2016). Profiling a cohort in the BA Degree in English at the University of Veracruz. In Paredes, B. & Chong (Eds.). Studies of Students Trajectories in Language Teaching Programs in Mexico. Publicaciones Académicas Plaza y Valdés.

Fernández-Cruz, E. B. & Narváez Trejo, O. M. (2021). The learning styles of pre-service teachers. CIEX Journ@l, 6(13), 31-41.

Freiberg Hoffmann, A. & Vigh, C. (2021). Enfoques de aprendizaje en estudiantes argentinos de nivel secundario y universitario. Diversitas: Perspectivas en Psicología, 17(1), 59-69.

Hall, T. (2002). Differentiated instruction. National Center. http://www.principals.in/uploads/pdf/Instructional_Strategie/DI_Marching.pdf

Horn, L., Nevill, S. & Griffith, J. (2006, April). Profile of undergraduates in U.S. Postsecondary education institutions: 2003–04 with a special analysis of community college students’ statistical analysis report. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED491908.pdf

Jourdan, C. E., Filippetti, V. A. & Lemos, V. (2022). Estrategias de aprendizaje y rendimiento académico: revisión sistemática en estudiantes del nivel secundario y universitario. Revista UNIANDES Episteme, 9(4), 534-562.

Kafadar, T. & Tay, F. (2014). Learning strategies and learning styles used by students in social studies. International Journal of Academic Research, 6 (2).

León-Sánchez, R. & Barrera-García, K. (2022). Enfoques y estilos de aprendizaje en estudiantes de psicología de una universidad pública en México. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte, (65), 102-136.

Marqués, D. V. D. A. P. & Días, C. (2010). (2010). The University as a knowledge reservoir – the comparative study of business and engineering undergraduate students’ profile of the Federal University of Goiás (UFG). http://eco.face.ufg.br/up/118/o/TD_021.pdf

Marton, F. & Säljö, R. (1976). On qualitative differences in learning: I. Outcome and process. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46, 4-13.

Medina, N., Del Valle Díaz, S., Rioja Collado, N. & Cuadrado Borobia, J. (2023). Evaluación del aprendizaje profundo metacognitivo y autodeterminado en estudiantes universitarios. Retos: Nuevas Perspectivas de Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 48.

Merriam, S. b. (1998). qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Narváez Trejo, O.M., Pichardo Nieves, G. & García Vázquez, D. I. (2019). Pre-service teachers’ approaches to learning. Paper presented at the Congreso Internacional de Investigación en Linguistica Aplicada. Cozumel, Quintana Roo.

Nunan, D. (2013). Learner-centered english language education: The selected works of David Nunan. Routledge.

Nunan, D. (1992). Research methods in language learning. Cambridge University Press

Núñez, P., Rodríguez, M. & Marcial, S. (2016). Newly Admitted Students Profile in an English BA program: language proficiency, and learning styles and strategies. Paper presented at the Foro de Estudios en Lenguas Internacional, Universidad de Quintana Roo.

O’Malley, M. J. & Chamot, A. U. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Heinle & Heinle Publications.

Oxford, R. & Burry-Stock, J. (1995). Assessing the language learning strategies worldwide with the ESL/EFL version of the strategy inventory language learning. System, 23, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251X(94)00047-A

Paredes, R. & Chong, W. (2015). Studies of student trajectories in language teaching programs in Mexico. Plaza y Valdés.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D. & Bjork, R. (2009). Learning styles. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

Rodríguez-Guardado, M. del S. & Juárez-Díaz, C. (2023). Relación entre estilos de aprendizaje y estrategias volitivas en estudiantes universitarios de lenguas extranjeras. RECIE. Revista Caribeña de Investigación Educativa, 7(1), 123-141.

Sánchez-Cotrina, E. (2023). Estilos de aprendizaje y autorregulación en estudiantes universitarios de Educación. Revista Científica Episteme y Tekne, 2(1), e479-e479.

Seliger, H. & Shohamy, E. (1989). Second language research methods. Oxford Applied Linguistics.

Thorpe, M. & Loo, R. (2003). The values profile of nursing undergraduate students: Implications for education and professional development. Journal of Nursing Education, 42 (2) 83-90.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2017). Differentiated instruction. In Fundamentals of gifted education (pp. 279-292). Routledge.

Tomlinson, C. A., Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Brimijoin, K. y Reynolds, T. (2003). Differentiating instruction in response to student readiness, interest, and learning profile in academically diverse classrooms: A review of literature. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 27(2-3), 119-145. https//doi.org/10.1177/016235320302700203

Torres-Zapata, Á. E., Acuña-Lara, J. P., Acevedo-Olvera, G. E. & Villanueva Echavarría, J. R. (2019). Caracterización del perfil de ingreso a la universidad. Consideraciones para la toma de decisiones. RIDE. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 9(18), 539-556.

Tulbure, C. (2012). Learning styles, teaching strategies and academic achievement in higher education: A cross-sectional investigation. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 33 (1), 398-402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.151

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo (s.f.). Perfil de ingreso y egreso from Licenciatura en Enseñanza de la Lengua Inglesa. https://www.uaeh.edu.mx/campus/icshu/investigacion/aala/lic_lenguainglesa/perfil_ingreso_egreso.html

Universidad de Guadalajara (2011). ¿Qué requisitos debo cubrir para ingresar a la licenciatura en docencia del inglés o didáctica del francés como lengua extranjera? http://www.cucsh.udg.mx/content/que-requisitos-debo-cubrir-para-ingresar-la-licenciatura-en-docencia-del-ingles-o-didactica-

Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango (s.f.). Perfil de ingreso y egreso. Retrieved from Licenciatura en Docencia de Lengua Inglesa, http://escueladelenguas.ujed.mx/ledli/perfil-de-ingreso-y-egreso/

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (2016). Portal de Estadísticas Universitarias. http://www.estadistica.unam.mx/perfiles/

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (2012). FES Acatlán: Enseñanza de Inglés. http://www.acatlan.unam.mx/licenciaturas/205/

Universidad Veracruzana (2016). Información estadística Institucional. La UV en números. http://www.uv.mx/informacion-estadistica/files/2014/01/UVennumerosmarzo2016.pdf

Universidad Veracruzana (2016, January). Anuario 2015. Información Estadística Institucional-Universidad Veracruzana. http://www.uv.mx/informacion-estadistica/files/2014/01/Anuario-2015.pdf

Universidad Veracruzana (2012, November 15). Requisitos de ingreso para la Licenciatura en Enseñanza del Inglés (virtual)-Licenciatura en Enseñanza del Inglés (modalidad virtual). http://www.uv.mx/inglesvirtual/aspirantes/requisitos/

Valle Arias, A., González Cabanach, R., Núñez Pérez, J. C., Suárez Riveiro, J. M., Piñeiro Aguín, I. & Rodríguez Martínez, S. (2000). Enfoques de aprendizaje en estudiantes universitarios. Psicothema, 12(3), 368-375. https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/7605

Wenden, A. & Rubín, J. (1987). Learning strategies in language learning. Prentice Hall International.

Willing, K. (1998). Teaching how to learn: Activity worksheets and teachers guide. NCELTR.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: design and methods. Sage Publications.

Zhou, M. (2011). Learning styles and teaching styles in College English Teaching. International Education Studies, 4 (1), 73-77. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v4n1p73